In a world like ours, where discussions of hunting are already full of pitfalls and confusions, “sport” and “recreation” only get in the way.

Tag: hunting

Eating and caring: The lines we draw

I think everyone holds some version of the same conceptual category: “Fellow creatures about whom I care too much to eat.”

Mindful carnivores here, there, and everywhere

The Mindful Carnivore has been spotted in the wild.

Food in an ideal world

What would your ideal, sustainable world look like?

An open letter to food co-ops

Why don’t food co-ops start selling hunting and fishing licenses?

Meat and meaning (or, Hunting on the brain)

The past few months have been crazy. I had the final six chapters of my book to draft. And I had a thesis to write.

The good and the slobby: Hunting, logging, living

Everyone I know—hunter or non-hunter—detests slob-hunting: Animals wounded carelessly or maliciously. Bodies and body parts dumped along roadsides. Shots fired at unidentified flashes of movement. And so on. We agree that such behavior is callous and wasteful, disrespectful and dangerous.

But why should it surprise us?

Recently, while revising a chapter for my book, I found myself reflecting on a couple of points made by writer and hunter Ted Kerasote in his essay “Restoring the Older Knowledge,” which I first came across in A Hunter’s Heart.

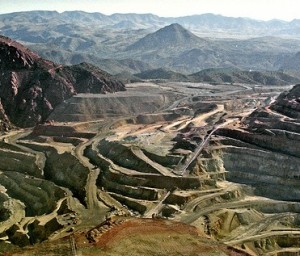

Kerasote notes that disrespect for nature and animals is not unique to thoughtless hunters. As a whole, he argues, our society operates with little regard for its impacts. From rapacious development, logging, and strip-mining to ecologically devastating agricultural practices and the application of toxic herbicides to suburban lawns, we inflict enormous damage. We do all kinds of things that are callous and wasteful, disrespectful and dangerous.

Kerasote argues, in short, that bad behavior among hunters is merely one facet of larger cultural patterns. It may be particularly visible and disturbing—for it is willful and impacts animals in an obvious, direct way—and it may therefore serve as a kind of lightning rod for disapproval, but it is not particularly unusual.

This doesn’t excuse such behavior. But it gives us a wider lens through which to see.

It helps me understand, for instance, why the question “Are you pro-hunting?” makes no sense to me.

One parallel: I have worked as a logger. If someone asks me whether I am “pro-logging,” I would say it depends. Do I approve of harvesting trees in a thoughtful, sustainable manner? Sure. Do I approve of laying waste to vast tracts of forest habitat? No.

Another parallel: I have also worked as a builder. If someone asks me whether I am “pro-construction,” I would say it depends. Do I approve of the modest timber-frame home my neighbor built for his family? Sure. Do I approve of starter castles, condominiums, and strip malls gobbling up high-quality farmland? No.

Now I hunt. Do I approve of killing a deer with as clean a shot as possible and eating the venison? Sure. Do I approve of shooting a couple hares for nothing more than amusement and leaving their bodies in the woods? Hell, no. (For lack of a wanton-waste law, I believe this remains legal in Vermont. And, yes, some people do it.)

Logging, construction, agriculture, hunting, you name it: Any activity can perpetuate the worst of who we are—humans at their greediest and most devastating. Or it can encourage the best of who we are—humans at their wisest and most respectful.

© 2011 Tovar Cerulli