Photo: A hunter stands in the woods, rifle to his shoulder, looking through the scope.

Caption: “All you can think about is how good this shot is going to feel.”

I saw the advertisement several years ago. I don’t remember if it was for the rifle or the scope. I don’t even remember what magazine it was in—I’m guessing Field & Stream. What I do remember is how much it bothered me. For most of the last year, it has been simmering on one of my mental back burners, a potential ingredient for a blog post.

Then, a few days ago, I got an email from Kevin Peer, drawing my attention to two ads that recently appeared in Bugle.

Curious, I flipped open the magazine to have a look. (I’ve been too busy to sit down with Bugle lately. Though I’ve never hunted elk—New England’s wild population was extirpated long ago—I joined RMEF to support their conservation work.)

The first ad, for Hodgdon Superformance rifle powder, pictured a white-tailed buck wall mount with a grotesque expression on his face: ears back, mouth open in a bizarre, surprised-looking grimace, tongue whipped to one side. The ad was titled “Speed Kills” and promised that “your next target won’t know what hit ‘em.”

The second ad, for Tikka’s T3 rifle, pictured a buck standing on an open plain. Encircling his neck was a wooden plaque, as if he was already taxidermied. The caption read, “What a Tikka hunter sees from 450 yards.”

I had a visceral negative reaction to the first ad. So did Cath, who does not hunt. She summed it up nicely: “That’s gross.” As Kevin said, the deer’s face was disturbingly comical, like something out of a cartoon. It made light of killing. Despite my macabre sense of humor and my appreciation for the occasional wisecrack about venison and Santa’s sleigh team, I did not find the image funny.

The second ad didn’t bother me as much, perhaps because it left the animal with some dignity and was tastefully composed in black and white. But I still had to agree with Kevin: It suggested that hunters can and should take 450-yard shots, particularly when a trophy is available for the taking. Not many hunters are capable of making a clean kill at that distance, no matter what rifle they’re using.

What concerns me is not any individual ad, magazine, or manufacturer. What concerns me is the big picture: all the ways we represent hunting.

Thinking about these things over the past couple days, I re-read Bill Heavey’s Field & Stream column from several years back, “Morons Among Us.” Heavey deplores an online post in which a guy complains that he didn’t get to entertain himself by humiliating a buck before the animal died. He deplores another post in which a bowhunter touts his success in shooting a doe in the brain. Firing an arrow at a deer’s head, Heavey notes, is “ethically indefensible”—the chances of a clean kill are far too small.

Compared to those gruesome posts, the ads I’ve mentioned are very mild. Subtly, though, aren’t they conveying similar messages?

Aren’t they saying that killing is comically entertaining (buck grimacing, tongue whipped to one side) and pleasurable (“All you can think about is how good this shot is going to feel”)? Aren’t they saying that it’s okay to shoot when the chances of a clean kill are small (the average hunter at 450 yards)?

Like Kevin Peer and Bill Heavey, I’m concerned about the future of hunting.

And I’m wondering: Can we afford the promotion of these values, even in subtle form? Can we afford their effect on current and potential hunters, both youth and adult? Can we afford the confirmation of non-hunters’ and anti-hunters’ worst suspicions?

When we see hunting portrayed in ways that disturb us, how should we respond?

One thing that struck Heavey: in those online forums, the two posts he mentioned were “met by a resounding absence of anger or censure.”

© 2011 Tovar Cerulli

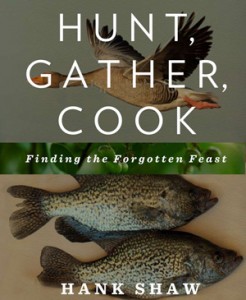

Just before the New Year, I was talking with a hunter I know. He mentioned how much he enjoys preparing venison for non-hunters. So often, they’re surprised by how good it tastes. Only one thing bothers him. After they declare it to be delicious, they’ll say, “I expected it to be gamey.”

Just before the New Year, I was talking with a hunter I know. He mentioned how much he enjoys preparing venison for non-hunters. So often, they’re surprised by how good it tastes. Only one thing bothers him. After they declare it to be delicious, they’ll say, “I expected it to be gamey.”

Sudden bouts of wondering why the local food co-op—with its cooler full of local, organic, free-range meats—doesn’t sell hunting licenses.

Sudden bouts of wondering why the local food co-op—with its cooler full of local, organic, free-range meats—doesn’t sell hunting licenses.

“Words of wisdom for vegans from hunters” – Hmmm. Unlike most of the other Googlers above, you might actually have come to the right place.

“Words of wisdom for vegans from hunters” – Hmmm. Unlike most of the other Googlers above, you might actually have come to the right place.