As I contemplated becoming a hunter, words helped.

As I contemplated becoming a hunter, words helped.

It was good, for instance, to read Richard Nelson’s introduction to A Hunter’s Heart.

There, I caught a glimpse of his journey: from a boyhood of believing that “hunting was entirely evil—no matter who did it, how they did it, or why,” to an adulthood in which hunting served to remind him that he was not separate from his fellow creatures but “twisted together with them in one great braidwork of life.”

But words only went so far.

Others’ words could suggest only what hunting had meant to them.

My own words could shape only questions: Now that I was eating fellow vertebrates again, would hunting help me confront their deaths? Would it deepen my relationship with the hills and valleys I call home? How would it feel to kill a deer?

Even in asking such questions, language felt too narrow. I could not describe the feelings that stirred inside me, let alone name the unknown force—what was it?—that called me to the woods.

If I had been a fine artist, I might have sought insight in paintings. If I had been a musician, I might have sought it in songs.

Being only an amateur craftsman, I sought it in things handmade.

When a cardboard box arrived in the mail, I took out the old knife, secured in a new sheath Uncle Mark had crafted for it. I contemplated the red buck he had painted on its front, and the black deer tracks hidden behind the haft. I reflected on the belt he had made, too, and the ancientness of the image scrimshawed on the antler buckle.

When a cardboard box arrived in the mail, I took out the old knife, secured in a new sheath Uncle Mark had crafted for it. I contemplated the red buck he had painted on its front, and the black deer tracks hidden behind the haft. I reflected on the belt he had made, too, and the ancientness of the image scrimshawed on the antler buckle.

Later, after I bought a secondhand caplock rifle, I took a pruned branch from one of our front yard apple trees—under which deer sometimes forage—and fashioned a ball-starter. With a woodburner, I sketched balsam twigs, the kind of cover through which I might stalk.

Later, after I bought a secondhand caplock rifle, I took a pruned branch from one of our front yard apple trees—under which deer sometimes forage—and fashioned a ball-starter. With a woodburner, I sketched balsam twigs, the kind of cover through which I might stalk.

With helpful tips from Mark, I made a powderhorn, too. Two deer stood in silhouette on its cherry plug. Crude lines etched into its side suggested Cold Brook, the rocky little waterway that tumbles through the woods behind our house, along whose banks I might look for tracks.

With helpful tips from Mark, I made a powderhorn, too. Two deer stood in silhouette on its cherry plug. Crude lines etched into its side suggested Cold Brook, the rocky little waterway that tumbles through the woods behind our house, along whose banks I might look for tracks.

Answers were still years away. But in these objects—in the variety of their shapes and textures and colors, in their symbolic and practical functions, in their very materials—the questions were given a fuller, more nuanced voice, specific to my hunting, here, in this place.

It’s hard to tell you what that voice said, though, muddling around within the constraints of these twenty-six letters.

© 2010 Tovar Cerulli

Don’t try too hard, some folks say. Desperation can drive the deer away. The less you expect, the more animals you see.

Don’t try too hard, some folks say. Desperation can drive the deer away. The less you expect, the more animals you see. Crouching beside him, I offered thanks and apology—poor compensation for what I had taken—and thought how strange this brief hunt had been. In years past, I had never even seen a buck on opening day.

Crouching beside him, I offered thanks and apology—poor compensation for what I had taken—and thought how strange this brief hunt had been. In years past, I had never even seen a buck on opening day.

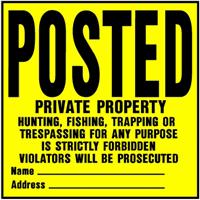

When Cath and I moved to our home here in the hills on the eastern side of the Winooski Valley, there was one group of people I wanted to keep off our few acres: hunters.

When Cath and I moved to our home here in the hills on the eastern side of the Winooski Valley, there was one group of people I wanted to keep off our few acres: hunters. I didn’t want to tempt fate by removing them entirely. In the previous few years, careless hunters had killed two bystanders in Vermont: one man picking berries where a hunter expected to see a bear, and another sitting in his living room watching television a long way from where a hunter missed a deer.

I didn’t want to tempt fate by removing them entirely. In the previous few years, careless hunters had killed two bystanders in Vermont: one man picking berries where a hunter expected to see a bear, and another sitting in his living room watching television a long way from where a hunter missed a deer.