Dear Community Food Co-ops of North America:

Maybe you’ve noticed. Adult-Onset Hunting™ (AOH) is spreading.

Maybe you’ve noticed. Adult-Onset Hunting™ (AOH) is spreading.

In the five months since my initial warning, additional reports have come in. In February, Monica Eng of The Chicago Tribune wrote about her first steps in becoming an “ethical carnivore.” Her symptoms are classic AOH. In April, Yes! magazine sent intern Alyssa Johnson into the field. Then came the news from Palo Alto: Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg may be afflicted.

What, you ask, does this have to do with community food co-ops? A lot, I think.

Consider Monica Eng’s words, for instance.

She cares about “sustainable food” and ecology, and isn’t keen on “giant toxic manure lagoons” polluting rivers and streams. She obviously cares about animal welfare, too, since she objects to animals being “crowded” and being forced to eat “unnatural diets.” And she wants to eat healthy food, not meat pumped full of “non-therapeutic antibiotics.”

Compare that with the criteria food co-ops often use in deciding what meat, poultry, and fish to sell:

- It must be wild, or raised in a humane way, ideally in free-range conditions.

- Production must be sustainable and environmentally friendly.

- No hormones or antibiotics can be used.

See what I mean?

So, how about it: Why don’t food co-ops start selling hunting and fishing licenses?

You don’t have to stop there, of course. You could also stock:

- crunchy granola bars for munchy hunters,

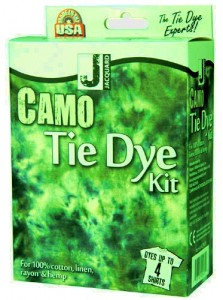

- tie-dyes and batiks in camo colors,

- organic lure and cover scents, building on product lines in your incense and aromatherapy sections,

- Birken-Stalk hunting shoes, as soon as the company catches on,

- and, naturally, books on hunting, food, and vegetarians-in-crisis.

I realize this may be a tough row to hoe. A lot of food co-ops started out as strictly vegetarian enterprises. The decision to start selling fish, poultry, and meat has been tough for many co-ops and their members. Believe me, I understand what you’ve been through.

I realize this may be a tough row to hoe. A lot of food co-ops started out as strictly vegetarian enterprises. The decision to start selling fish, poultry, and meat has been tough for many co-ops and their members. Believe me, I understand what you’ve been through.

Hunting may seem like alien cultural territory. But consider what one food co-op, just an hour from here, says about how co-ops began: “Early human societies learned to cooperate and work together to maximize their efficiency for hunting, fishing, gathering foods, building shelter, and meeting their individual and collective needs.”

Hmmmm. Hunter-gatherer societies as the original food cooperatives.

If it really is alien cultural territory, all the more reason to go there. I’ve noticed that a lot of food co-op mission statements mention a commitment to “diversity.” And ideological diversity, after all, is the hardest and most important kind to practice.

Sincerely,

A Mindful Carnivore (Member, Hunger Mountain Food Co-op)

© 2011 Tovar Cerulli

Birken-Stalks – LOVE IT! And I wouldn’t be at all surprised to see signs of this in SF, which is a hotbed of ethical carnivory.

Now we know what to call them anyway (the shoes and the especially-crunchy hunters): Birkenstalkers.

Snort! Good post as always but the Birken STALK broke me up. I’m teary now.

Glad I could bring a tear to your eye, Annette. 😉

And the #1, I mean the best meat counter in the Upper Valley is the Lebanon Food Coop.

Thanks for commenting, Bill. I’m trying to recall whether I’ve ever been in the Lebanon store. I’ll have to check it out sometime.

I could go for the Birken-Stalks (especially good for stalking in the birches), but with my feet I’d need a pair with scent-lok. (Or scent-lok socks???) And the camo tie-dye scheme sounds like a good way to save money on the monthly Cabela’s bill. Hmmmm…

If you have a “monthly Cabela’s bill,” then you’re probably beyond hope. Your feet? You need the Birkenstalker-Locker model.

Recently Cabelas started offering cork sole boots which look like Birkenstock Rockford knockoffs. I use the Rockford which at one point was rated #1 by backpacker magazine. These are the best boots I’ve ever worn and so comfortable, you want to wear them to bed.

There’s already a cross-over boot out there, Sam? Great!

Okay, Tovar, we all want Birken-Stalks now. You do realize you’re committed to starting the company?

Hmmm. Maybe Birkenstock would like to start a subsidiary.

Great post! It’s not my crowd, but it’s the crowd I’m helping to get involved in hunting, so more power to ’em!

I love our Co-op, and I will send them straightaway to your site, Tovar.

I imagine no co-op will take my suggestion seriously, but it’s a fun idea to play with.

You could go one step further and change the law so that hunters could sell game in those co-ops. I suppose the lack of an USFDA inspection would be a hurdle.

I’d be awfully leery of turning hunting into a cash-for-meat enterprise. That seems fraught with all kinds of dangers: market-hunting pressure on animals, competition among hunters, etc. In some places, I understand that people have drawn guns on each other over territory for gathering wild plants and mushrooms (for cash sale). How much worse would that be among hunters?

I think it’s just another one of those two-faced things about hunting. We sell fur from trapping. Local anglers sell perch and other fresh water fish. We have an entire commercial fishing industry. But heaven forbid, we allow the sale of deer meat. The situation even makes less sense in the context of dwindling hunter numbers, out of control deer populations, and a growing market for deer meat.

You’ve got a point about situations where deer populations are not being effectively managed.

Commercial fishing, however, might not be a model we want to emulate on land. Like the North American market hunting of the 1800s, globally it hasn’t been very well managed and has devastated a lot of fish populations.

Sam, I’m really of two minds about this. On the one hand, market hunting was really a huge part of why a lot of species diminished to nothing or went extinct, so it’s a dangerous enterprise where wildlife is concerned. On the other hand, the lack of market hunting here has created a public that is highly ignorant of game meat. Contrast that with Europe, where in many places you can go to the local farmer’s market or butcher shop and buy wild hare or pheasant. I think the limited availability of game meat contributes to a lack of understanding in the public of what we do.

All that said, I’m 99 percent sure we’re going the other direction. Market hunting has ended. There are, in some places, some limits on foraging, but that may not be enough. And I wouldn’t be at all surprised to see commercial fishing end in my lifetime. There are just too many of us to let wild food satisfy everyone’s demands.

I agree that farming is the only way to feed the population but I don’t think commercial fishing will end because of the people that differentiate wild and farm raised flavor. Similar set of circumstances with deer farming and deer hunting. Market hunting of the past had little or no regulation. Commercial fishing is a global regulatory problem. Both are examples from which to take what works and leave behind what doesn’t. I really don’t have a problem with it as long as the resource isn’t clobbered.

I think the resource IS being clobbered…

The original inhabitants (human) lived a tough life of the land, weather, and the wim’s of nature molded them into survival machines. Territory big enough to sustain their needs and wants was defended brutely with power shifts and culling of the competition. Mass farming, has only temperarily eased tentions in territory and space. New york city’s land does not support it’s population and it may seem nice to help out the neighbors and they may benefit us one day, but isn’t it “Unnatural”to help the competetion? Is it not nature’s way to maintain advantages and ensure ones genes survive? A move back to nature seems nessesary yet if all made the move would it not spell the end for her? How will man decide his fate, singley or collectively? Will our knowledge of nature’s supreme rules be lost? Should people living below sea level be surprised by salt water? Will society revert back to tribe life, as populations decrease and our mass farming culture collapses? Nature finds a way, will she be her brutal old self? More then likey!

I have to echo Holly’s and Tovar’s sentiments about market hunting. I hope the history of wretchedness that ensued pre-1930s in this country, is enough to forever dissuade us from returning to that market model. Furthermore, we don’t have the type of economic regulatory environment (generally speaking) that European countries and the EU have had. Even then, the very bad situation in Malta, for instance, where protected European migratory birds and raptors are being shot for profit, is affecting European bird populations.

If you look at global wildlife trade in areas like Asia, the availability of exotic foodstuffs in markets, the demand for even legal animal parts, and the profits to be earned from illegal parts, has led to out-of-control wildlife trafficking that is having serious, deleterious effects on global wildlife populations. Allowing some invites a free for all in so many cases. Of course, as Tovar and Holly mention, you need only look at worldwide commercial fishing for a cautionary tale.

One last thing: For profit animal endeavors almost always lead to abuses, whether they are economic, environmental or abuses toward the animals themselves. You mention trapping as a commercial endeavor for some. Some of the worst wildlife abuses I’ve seen have to do with trapping animals for pelts. I cringe to see an expansion in what humans can do to wildlife for the sake of money. As far as I’m concerned, there’s enough of that without additional commercial incentive.

Although, as a non-hunter, I’m not happy with how our wildlife issues are managed a lot of the time. I’ll take our system, thank you.

” For profit animal endeavors almost always lead to abuses…”

Yep – witness factory farming.

Maybe you’ve noticed. Adult-onset hunting (AOH) is spreading.

Yes, much to my chagrin. 🙂 I don’t give up hope, though, that as this cycle progresses, eating less meat is actually the outcome, along with a reduction in factory farms. I don’t quite see how our wildlife can sustain a huge number of new hunters, though. That troubles me. But I am not as hard-lined as people might believe, based on my comments here. I think Pollan’s approach is the most sane: eat mostly vegetables, with meat as a condiment. That alone would be a significant, global change in terms of how we utilize our land and treat other animals.

Ingrid —

I agree that it would be hard for our wildlife to sustain a HUGE number of new hunters. But right now AOH could help prevent hunter numbers from falling too far. All other trends point to the likelihood of that happening during the years to come. When it comes to species like whitetail deer, hunting is the pretty much the only tool we have for restoring the balance we’ve disrupted.

Yesterday I interviewed a botanist who’s an expert on the impact of overabundant deer on the forest ecosystem. I saw some of his study areas, including one property that had been a wildlife refuge with no hunting allowed over a period of decades. Deer had reached a density of over 100 per square mile, and you didn’t have to be a scientist to see the ecological consequences. The forest understory was completely gone. There wasn’t a squirrel or a bird anywhere.

Then when I got home last night, I was flipping through the mail and saw an article predicting major declines in hunter numbers over the next 20 years. So I’d say AOH, if it really is becoming an epidemic, could be a very good thing.

Hey, Al, I was typing my reply below at the same time you were typing yours. Good points.

There is irony here, though. Hunters, after all, have helped create the overpopulation problems to which hunting is now the main solution. Here in Vermont a hundred years ago, farmers wanted very aggressive hunting seasons to keep the deer population down to almost nothing (in the first modern season in 1897, 103 bucks were tagged in the entire state). Hunters, on the other hand, wanted to let deer populations recover. I’m not saying hunters intended to end up with 30 or 50 or 100 deer per square mile (and, by and large, that hasn’t happened here in VT), or to wipe out the understory and hammer bird and amphibian populations. But hunter-driven wildlife policies have, arguably, helped create these situations.

Helped in the past and perpetuate. The hunting community in VT has all but handcuffed farmers from being able to protect their crops. They can only shoot 3. It used to be unlimited as long as the farmer could show damage. There was legislation brought up this year to allow tree farmers to cull 6 deer because of damage, but it didn’t go anywhere. Apparently deer populations have reached a level where timber producers are now seeing stunted sapling growth because of deer. The FWD says there is 25/sq mile along the entire Champlain Valley. Three isn’t much of dent in 25. The ironic part is that any culling activity from hunting is after the fact. Hunters don’t take to woods until it’s too late. And come the following spring, new fawns put the deer population back to damaging numbers. Laws have been created to ensure that the deer population is the highest it can be regardless of consequences.

Good points there, Sam.

I think AOH is spreading in the American psyche. I hope this is making people realize that hunters and hunting are as complex as anything else, and aren’t just stereotypes. I also hope it reflects a growing and deepening awareness of our impacts on animals and nature: a willingness to be honest with ourselves and to make our impacts less gratuitous.

In terms of actual numbers of hunters, I’d be surprised if it has a huge impact. Nationwide, numbers are still on the decline, I believe.

Even if there was a real uptick in the number of hunters, “game” animal populations are unlikely to be seriously impacted. Wildlife managers keep a careful eye on them. Here in Vermont, for instance, the number of tags available for hunting antlerless deer go up and down every year in every section of the state, depending on whether deer are heavily overpopulated, just endured a harsh winter, etc. Whatever our opinions of hunting or of hunter-driven conservation models (and mine remained mixed), there’s one thing that the past hundred years have shown: If hunters value an animal as prey, that animal is going to thrive.

And, yes, the average American diet is still heavy on the meat. (I still eat a lot of salads and grains, so my blog and book could be called “The Mindful Omnivore.” But Pollan already has the corner on “omnivore.” And “Mindful Carnivore” is, of course, more provocative.)

Tovar – this is all true, but I would take it a step further. In some areas we need more hunters and hunting. Exurban areas have too many deer, largely because of the breakup of the land, where there are enough areas to hide and lots of food. Deer are a “creature of the edge”. Also, geese are way out of control in many areas of the country and there are getting to be lots of wild turkeys in many suburbs. Of course, there’s the wild pigs, which we don’t have in MN (yet). The “locavore hunter” movement has a simple, but true, logic to it based on current circumstances. As a general matter, the planet is being overused and destroyed, but in a number of areas there are plentiful game animals that actually need to be hunted living close to lots of people. I love my (rare) wilderness hunts, but I do a lot of my hunting 45-50 minutes from house near downtown Minneapolis, my other spots are just under two hours.

That, too, is all true, Erik. It’s a complex picture!

“”I don’t quite see how our wildlife can sustain a huge number of new hunters, though.”

It doesn’t have to, Ingrid. Hunting is the only means of meat acquisition that is BY LAW sustainable. Limits are based on what herds, flocks, etc. can sustain. If the hunting population started increasing noticeably, regulatory agencies would pretty much automatically start dialing back on limits.

That, in turn, would check the growth in hunters. There’s NO FREAKIN’ WAY I’d hunt ducks if I could get only 2-3 per year. Duck hunting takes so much investment that I need a bigger return than that.

And public lands would become so crowded that hunters would back away. (We know this for fact, because one of the things that causes a lapse in hunting is loss of places to hunt. Losing a public place to private ownership or development is one way that happens; another is when public land becomes so crowded that access is de facto limited.)

Agreed on all of the above, Holly.

Open question, on this topic, to Tovar, Holly and anyone who wants to chime in.

I know we’ve spent a lot of time doing the back-and-forth between your hunting views and my non-hunting views. But I’m not sure I really know what your ideal, sustainable world looks like. That is, within the paradigm that you support — hunter, gatherer, locavore (gawd I hate that word) — what solutions do you see that would, 1) actually work, given our huge global population, 2) truly manage our resources well, 3) reduce our ecological imprint, and 4) not incur, and maybe even reduce, the suffering we inflict on other species (because I think that is, indeed, part of a conscious, sustainable world).

My baseline frustration in any ecological model, one I probably I share with many of you, is that population issues are the elephant in our global living room. Actually, it may be more our national issue since we seem to be in denial about how our consumption over-population affects the world at large. I don’t think any truly sustainable planet can emerge unless we address population matters effectively. And, unfortunately, like almost every other matter involving lifestyle and choice, it’s laden with emotion that gets in the way of pragmatism.

p.s. I’m serious about entertaining options other than the ones I tend to advocate. If there is a way to make this planet work better for all of us, humans and non-humans alike, I’d rather work toward that with some sense of compromise, than fight for an unattainable ideal.

My ideal world cannot exist with our current population or anything close to it. I’d like to see us knocked back to about 12,000 B.C. I know – that means no blogging. But I think that was sustainable (even though, as you know from posts on my blog, I recognize that our species has always been on this course, even when we LOOKED more sustainable).

I also believe this problem will ultimately resolve itself, because at some point, we will find ourselves utterly unable to continue thwarting natural processes, and our species will be drastically reduced, if not wiped out completely. The earth will go on just fine.

I’m with you Holly. A big part of me would like to see a return to much simpler times as well.

Ingrid, my ongoing goal in life is to set my family up on a nice plot of land and get off the grid by using solar, wind and geothermal technologies built into as much of a self-sustaining, energy efficient home as possible. Ideally I could also add a hobby farm with a chicken coup, a couple of dairy cows and bee hives probably. I’d hunt my own land for my meat and grow the largest variety of fruits and veggies in my garden as possible, using them for primary sustenance.

I think if we could all live like that, the load on our planet would be vastly reduced. Unfortunately – as you said – the population is out of control and (barring a pole reversal or some other apocalyptic event 😉 I believe its far too late for the widespread acceptance of such ideas for daily living among modern, first-world societies.

Too many people in the world define their worth through their possessions, or how closely they can identify with fictional (and some sadly real) characters on television.

There’s also too much money at stake for the world to become truly sustainable. Sustainability is in direct opposition to capitalism. You can’t make money on things that don’t need to be repaired, replaced or maintained on a regular basis, that’s why a society built on capitalistic values can never truly be fully sustainable.

Hate to be a downer but I’m pretty convinced that its already too late to turn this big a** ship around.

Love your vision, Kevin. I think chickens are the only meat animal I’d want to raise (and keep for eggs too). I’d do goats for milk – they’re plenty productive, useful for controlling undergrowth, smart, and fun. But yeah, off-grid, lots of hunting and foraging? Heaven!

I know, the earth will go on just fine without us, and it will resurrect itself, eventually, in the wake of our damage and carnage. But in the meantime, so much suffering will result from our inability or unwillingness to change what can be changed. I’m a horrible cynic, the true definition of the frustrated idealist. But the idealist in me hasn’t died, because I do believe that individual effort begets cumulative effort begets cumulative desire. And that it matters. It goes back to the thing Hugh always reminds me of when I feel utterly despondent over how many animals I can’t help: “it matters to that one animal that you helped him or her.” What I fear in global resignation over our fate, is that people will do as they will, feeling no hope about the outcome, when, in fact, there is much that can be done to ease the burden just a little while we’re here. And to that end, I think sustainable models are important in terms of the quality of life we and others (human and non-human) experience while we’re here … even in the face of what appear to be insurmountable challenges … even if we’re destined, ultimately for our own destruction. I see things everyday that challenge my ability to even function, given how awful things look. But maybe it’s the Capricorn in me that keeps plodding along like a good goat with some semblance of hope.

“Maybe it’s the Capricorn in me that keeps plodding along like a good goat with some semblance of hope.” That’s probably true of me, too.

For what they’re worth, I’ll chime in with my two cents on these more global questions over the weekend…

The weekend got away from me. Then, this morning, I started typing up my reply to your question, Ingrid. Before long, I had written over 500 words.

If you all don’t mind, I think I’ll do some editing and turn it into its own blog post, with reference to Ingrid’s question, as well as to Holly’s initial reply and Kevin’s.

Related/unrelated rant: While getting co-ops, the vegan community, environmentalists, assorted hippies to be more accepting and open to responsible, ethical hunters- equal work has to be done convincing sportsmen (mostly hunters) of the opposite-vice versa. It’ll be much harder accomplishing the latter. The conservation-minded hunters aren’t the problem obviously. It’s the shooters (not hunters- just lunatics with guns that like to kill and spill blood). It’s probably a lost cause. They don’t see the connection between nature, environmentalism and hunting. They loathe tree-huggers. They’d rather cut their nose to spite their face than be associated or be in agreement with environmentalists. It’s a complex issue deep rooted in politics, 2nd amendment-phony conservation groups and social stigma. It’s a shame. The hunter should be the ideal environmentalist- but the disconnect is just way too significant.

Also- I don’t think substantial increases in the number of new hunters and anglers is something that should be encouraged. Maybe that’s me being somewhat selfish- I don’t know. Yes, the license fees would be wonderful for conservation. But, with all the commercial development (even residential) out there, sprawl, decreasing habitat, crowded public hunting lands- we’ll end up wiping out the populations of wildlife and sending more sportsmen home without food. We can’t turn back the clock and live the way we were meant to as humans. A mass hunter-gatherer society cannot exist today. While the romantic idea of turning back the clock with some apocalyptic event causing us to live like our ancestors did sounds nice, in reality, we’d probably wipe out wildlife populations clean in a single season. There’s too many damn humans in this world. IMO, there’s a need for factory farms in our society. Factory farms need to invest in their operations for the sake of the environment and public health. I don’t know how realistic it is. Stop the filthy living conditions, hormones and antibiotics and implement better environmental practices to reduce pollution, wastewater contamination etc. The Purdues of the world can serve a good purpose.

I’d like to see the existing population of sportsmen be more conservation-minded, environmentally-conscious and traditional in their skills & ability. But do I want to see more hunters and anglers out there- definitely not. The world can start eating healthier and in a more sustainable matter without picking up a gun or rod.

How’s this for an equation (based on our current political climate): More people turned on to hunting=More gun and ammo purchases=More NRA money and more gun lobbyists= Increases in their lobbying and political contributions=More anti-conservation politicians= 1. Bigger decreases in taxes: Cuts to conservation funding which results in vanishing habitat. 2. More hand-outs to developers, energy companies etc. That paints a pretty bleak picture for the future of hunting & fishing in America.

I don’t think more hunters mean more NRA money or necessarily more conservative, hence anti-public sector and anti-conservation politics. There is a sigificant disconnect between a large swath of hunters who believe in 2nd amendment rights/private firearm ownership rights, but have a pretty practical view of guns, and NRA members and the gun-rights movement. The Joe hunter types see a firearm as a tool, a very powerful one, so of course there are responsibilities involved with having them, but of course the gun’s deadly power does not mean it can’t be an instrument of joy and satisfaction. Most NRA members believe (despite their official stance that guns are a tool) that guns have an inherent value, they are really GOOD things (they are always an instrument of freedom and security, based on their use in the American revolution). Many NRA members are NOT hunters, and the organization does a lot of things that are outright anti-hunting, something an outdoor reporter told me off the record, which I then started to observe myself. I do know a few NRA members who are environmentalist/conservationist, and their membership is driven by disliking the other side (anti-gun people or gun control groups) than the NRA and feel they have to be somewhere. Plus, the NRA has good programs for teaching people how to use guns safely and effectively.

I think it depends where the new hunters come from in terms of what effect they have on coalitions with environmentalists who don’t hunt or fish. Even so, conservative hunters are more willing to pay for conservation than other conservatives who don’t hunt. Not that your point isn’t true. Sara Palin loves to hunt but has anti-hunting politics. Seems to me we have to make that point louder and more persistently. It worked for our current governor in MN, a liberal Democrat who is a casual hunter and angler. He pretty effectively defeated his GOP opponent, an avid hunter, amongst hunters, because his GOP opponenet had opposed a dedicated tax increase for wildlife habitat supported by hunting groups.

As far as this post, where I’m at some of the ideas aren’t that far of a leap. The Minneapolis and Saint Paul co-ops had some of the first organic meat counters in the nation, and they were and are highly successful. Our co-op has classes on all sorts of skills that help you be more environmentally friendly, from gardening to bike repair. I’ve thought about proposing a hunting class or writing an article for the newsletter, I just haven’t gotten around to it. I can say as far as the staff a the co-op, I have never experienced any hostility towards hunting or me because I’m a hunter. I know for a fact that a number of members are hunters. However, I would guess MN and WI are the states where that cross-over is less challenging: liberal states with high hunting participation. There are probably other factors at work, like the fact that there are a lot of city folk with rural backgrounds.

I considered mentioning “hunting classes” in this post, to go along with all the other skill-building classes being offered through food co-ops these days…

Your questions are good ones, SAF, as is the one you posted over on Facebook, about whether hunting companies and stores are offering environmentally-friendly products.

I agree that it’ s important to get more hunters into an environmental mindset, and that it’s not easy. (If you haven’t seen it, check out my post from last summer about Susan Morse.)

As I said above, I don’t think we’re likely to get a truly substantial increase in the numbers of hunters. If that were to happen, as Holly and I both argue above, there are regulatory mechanisms in place that would prevent a “wiping out” of wildlife populations. I totally agree with you, though: “A mass hunter-gatherer society cannot exist today.” And I’m not sure that a post-apocalypse mass hunter-gatherer society would be a good thing either.

I agree with Erik: New hunters’ effects on “coalitions with environmentalists who don’t hunt or fish” depends on where those new hunters are coming from.

Years ago it seems as though a rift formed: The bambification of ecology on the left, and a growing disdain for said environmentalists, and environmentalism in general, on the right, which oddly ended up including many of the rural hunting population. Re-unifying these two natural allies seems like a good benefit to all. Thanks, Tovar, for trying to build a bridge.

To comment on some subsequent posts, I feel pretty strongly about the idea of the harvest of natural resources. Some parts of the east do indeed have loads of deer, but I have to come down pretty heavily on the Bad Precedent side of the discussion. Deer here in California have actually reduced considerably, due to a number of factors.

What we are seeing though, is a huge increase in plant foraging both personal and commercial. I have spoken with longtime mushroom pickers about the situation, and as much as I like wild mushroom on the menu I can see where it’s going. One local company was even offering “foraging CSA” boxes. This is a great recipe for screwing up a resource. I would have to say we all belong to a co-op for meat and wild edibles; learn, and go out and find it yourself. This is almost self regulating since one has to pay their dues to join, and not in money.

A greater awareness of the interrelationship of land to food, hunting and gathering being the most direct connection, is only good for encouraging others to see this connection even if they don’t partake in hunting or foraging. In San Francisco, hunting is far, far more popular in theory that practical fact. Most won’t ever go hunting or foraging, but instead play out this awareness in other ways. This is a good thing, I think.

The by-product of this is good for hunters. As wilderness is more often cut into pockets between human settlements, a greater sense of interaction and cooperation between hunters and non-hunters is necessary. I am very conscious of this, and have had some wonderful opportunities close to my urban home as a result. Hunters in general need to remember that they are ambassadors for more than just themselves. Like most diplomatic missions, it requires some give and take on small issues to gain on the larger ones. As more wilderness is given over to land trusts in order to be preserved, creating a sense of being part of the solution is necessary if we want to remain a central part of conservation. (And SportsmenagainstFracking is dead-on in his observation on this.) It is amazing that watersheds and conservation land trusts pay thousands if not millions of dollars to reduce wild pigs, and that meat is generally wasted. A good partnership with hunters, such as California’s SHARE program, would be an easy and inexpensive solution if the public goodwill could be nurtured.

Excellent points, Neil.

Thanks, Tovar. One thing: when I say “harvest of natural resources” I mean commercial harvest. I enjoy your blog, keep it up.

As you may know, Neil, there are groups working to conserve wild plants that have been heavily harvested. United Plant Savers, for instance, was founded by herbalists and focuses on protecting wild medicinal plants: a good example of restraint practiced by those who were doing the harvesting and recognized the dangers.

I have hunted since I was a young girl and I taught hunter education for the state of Arkansas for 12 years. If we are to see hunting continue it is important to bring women and more “adult onset hunters” to the sport. Hunter numbers are dropping and in many areas they are needed more than ever. Many cities in Arkansas have now opened special bow seasons because of overpopulation. Since we have eradicated many of the large predators in the lower 48, it is important for us to step our role, and we can do it for our own betterment as well as for the creatures we hunt.

Hunters Feeding the Hungry is an excellent program. I have not participated in it myself, but these last few years I have used leftover tags to harvest animals for needy families. The herd benefits, the family benefits and I get more time in the woods. The Elks club also has an excellent program for disabled veterans. They will accept your hides and have them made into leather, then gloves for wheel chair bound veterans. I participate in this, as well.

I do worry about the future, however. We are no different than the animals we pursue. There soon will be far more of us than the habitat will support…

Good points, Carol. I think adult-onset hunters can add (at least slightly) to the number of hunters. Perhaps more important, I also think they can add to the diversity among hunters (gender, ethnicity, ideology, etc).

Do you know if the Elks club runs that program nationwide?

Tovar, I am not certain about the Elks program. My neighbor is a member and next time I see him, I will see if he knows.

Yes, the program is national.

Thanks, Carol. I’ve sent an email to the local lodge, to see if they participate.