The past few months have been crazy. I had the final six chapters of my book to draft. And I had a thesis to write.

Category: Uncategorized

The good and the slobby: Hunting, logging, living

Everyone I know—hunter or non-hunter—detests slob-hunting: Animals wounded carelessly or maliciously. Bodies and body parts dumped along roadsides. Shots fired at unidentified flashes of movement. And so on. We agree that such behavior is callous and wasteful, disrespectful and dangerous.

But why should it surprise us?

Recently, while revising a chapter for my book, I found myself reflecting on a couple of points made by writer and hunter Ted Kerasote in his essay “Restoring the Older Knowledge,” which I first came across in A Hunter’s Heart.

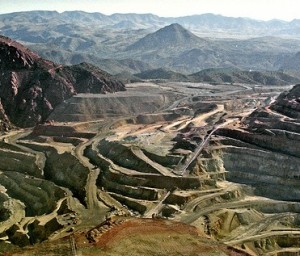

Kerasote notes that disrespect for nature and animals is not unique to thoughtless hunters. As a whole, he argues, our society operates with little regard for its impacts. From rapacious development, logging, and strip-mining to ecologically devastating agricultural practices and the application of toxic herbicides to suburban lawns, we inflict enormous damage. We do all kinds of things that are callous and wasteful, disrespectful and dangerous.

Kerasote argues, in short, that bad behavior among hunters is merely one facet of larger cultural patterns. It may be particularly visible and disturbing—for it is willful and impacts animals in an obvious, direct way—and it may therefore serve as a kind of lightning rod for disapproval, but it is not particularly unusual.

This doesn’t excuse such behavior. But it gives us a wider lens through which to see.

It helps me understand, for instance, why the question “Are you pro-hunting?” makes no sense to me.

One parallel: I have worked as a logger. If someone asks me whether I am “pro-logging,” I would say it depends. Do I approve of harvesting trees in a thoughtful, sustainable manner? Sure. Do I approve of laying waste to vast tracts of forest habitat? No.

Another parallel: I have also worked as a builder. If someone asks me whether I am “pro-construction,” I would say it depends. Do I approve of the modest timber-frame home my neighbor built for his family? Sure. Do I approve of starter castles, condominiums, and strip malls gobbling up high-quality farmland? No.

Now I hunt. Do I approve of killing a deer with as clean a shot as possible and eating the venison? Sure. Do I approve of shooting a couple hares for nothing more than amusement and leaving their bodies in the woods? Hell, no. (For lack of a wanton-waste law, I believe this remains legal in Vermont. And, yes, some people do it.)

Logging, construction, agriculture, hunting, you name it: Any activity can perpetuate the worst of who we are—humans at their greediest and most devastating. Or it can encourage the best of who we are—humans at their wisest and most respectful.

© 2011 Tovar Cerulli

Kill-humor, long shots, and the future of hunting

Photo: A hunter stands in the woods, rifle to his shoulder, looking through the scope.

Caption: “All you can think about is how good this shot is going to feel.”

I saw the advertisement several years ago. I don’t remember if it was for the rifle or the scope. I don’t even remember what magazine it was in—I’m guessing Field & Stream. What I do remember is how much it bothered me. For most of the last year, it has been simmering on one of my mental back burners, a potential ingredient for a blog post.

Then, a few days ago, I got an email from Kevin Peer, drawing my attention to two ads that recently appeared in Bugle.

Curious, I flipped open the magazine to have a look. (I’ve been too busy to sit down with Bugle lately. Though I’ve never hunted elk—New England’s wild population was extirpated long ago—I joined RMEF to support their conservation work.)

The first ad, for Hodgdon Superformance rifle powder, pictured a white-tailed buck wall mount with a grotesque expression on his face: ears back, mouth open in a bizarre, surprised-looking grimace, tongue whipped to one side. The ad was titled “Speed Kills” and promised that “your next target won’t know what hit ‘em.”

The second ad, for Tikka’s T3 rifle, pictured a buck standing on an open plain. Encircling his neck was a wooden plaque, as if he was already taxidermied. The caption read, “What a Tikka hunter sees from 450 yards.”

I had a visceral negative reaction to the first ad. So did Cath, who does not hunt. She summed it up nicely: “That’s gross.” As Kevin said, the deer’s face was disturbingly comical, like something out of a cartoon. It made light of killing. Despite my macabre sense of humor and my appreciation for the occasional wisecrack about venison and Santa’s sleigh team, I did not find the image funny.

The second ad didn’t bother me as much, perhaps because it left the animal with some dignity and was tastefully composed in black and white. But I still had to agree with Kevin: It suggested that hunters can and should take 450-yard shots, particularly when a trophy is available for the taking. Not many hunters are capable of making a clean kill at that distance, no matter what rifle they’re using.

What concerns me is not any individual ad, magazine, or manufacturer. What concerns me is the big picture: all the ways we represent hunting.

Thinking about these things over the past couple days, I re-read Bill Heavey’s Field & Stream column from several years back, “Morons Among Us.” Heavey deplores an online post in which a guy complains that he didn’t get to entertain himself by humiliating a buck before the animal died. He deplores another post in which a bowhunter touts his success in shooting a doe in the brain. Firing an arrow at a deer’s head, Heavey notes, is “ethically indefensible”—the chances of a clean kill are far too small.

Compared to those gruesome posts, the ads I’ve mentioned are very mild. Subtly, though, aren’t they conveying similar messages?

Aren’t they saying that killing is comically entertaining (buck grimacing, tongue whipped to one side) and pleasurable (“All you can think about is how good this shot is going to feel”)? Aren’t they saying that it’s okay to shoot when the chances of a clean kill are small (the average hunter at 450 yards)?

Like Kevin Peer and Bill Heavey, I’m concerned about the future of hunting.

And I’m wondering: Can we afford the promotion of these values, even in subtle form? Can we afford their effect on current and potential hunters, both youth and adult? Can we afford the confirmation of non-hunters’ and anti-hunters’ worst suspicions?

When we see hunting portrayed in ways that disturb us, how should we respond?

One thing that struck Heavey: in those online forums, the two posts he mentioned were “met by a resounding absence of anger or censure.”

© 2011 Tovar Cerulli

Accounting for taste: What’s with “gamey”?

Just before the New Year, I was talking with a hunter I know. He mentioned how much he enjoys preparing venison for non-hunters. So often, they’re surprised by how good it tastes. Only one thing bothers him. After they declare it to be delicious, they’ll say, “I expected it to be gamey.”

Just before the New Year, I was talking with a hunter I know. He mentioned how much he enjoys preparing venison for non-hunters. So often, they’re surprised by how good it tastes. Only one thing bothers him. After they declare it to be delicious, they’ll say, “I expected it to be gamey.”

“I’m so tired of people saying they expect it to be ‘gamey,’” he told me. “Venison is about the nicest meat I can imagine.”

A few nights later, a couple of friends were here at our place for dinner. Among the dishes on the table was a bowl of venison meatballs. I told one of our guests how fond Cath is of that particular recipe. “Oh,” he asked, “does it help get the gamey flavor out?”

The gamey flavor. What is with that?

Is this notion stuck in people’s heads because they’re freaked out by the idea of eating wild animals? Is it rooted in cultural and economic history, in the feeling that game-consumption is a sign of poverty?

Are people speaking from experience? Have they been subjected to horrendous cooking? Have they been traumatized by eating venison that was poorly processed, or was “aged” until it turned green? (For a not-so-scientific investigation into the effects of such handling, see “The Taste Controversy Ends” from the U.S. Venison Council.)

I don’t know. Maybe it’s just me. Maybe, in my decade as a vegan, I simply forgot what domestic meat tastes like.

Cath and I do eat plenty of local chicken and turkey, but when it comes to red meat, venison is the only flavor I really know. When the weather warms, I’ll be slicing thin strips of backstrap, sautéing them lightly, and serving them over fresh salad greens from the garden. Cooking venison this way doesn’t get rid of any of the flavor, thankfully.

Maybe there’s nothing wrong with beef, but I expect it might taste farmy.

© 2011 Tovar Cerulli

Wounded animals, Uncomfortable hunters

![]() Back in November, a fellow hunter and I talked about an essay he’d written. In it, he described stumbling onto a deer that had been wounded by someone else. When the piece was published, he heard from some disgruntled hunters. They didn’t like seeing that kind of story in print.

Back in November, a fellow hunter and I talked about an essay he’d written. In it, he described stumbling onto a deer that had been wounded by someone else. When the piece was published, he heard from some disgruntled hunters. They didn’t like seeing that kind of story in print.

A couple months later, I was at a public hearing about hunting. During it, a woman voiced concerns about the wounding and loss of deer and moose in archery seasons. When she spoke, disgruntled hunters started muttering loudly. They didn’t like hearing that kind of talk.

A month after that, a filmmaker and I talked about a film she’d made. In it, she showed several hunting scenes, including one where the animal did not go down with the first shot. When the film was shown, she heard from some disgruntled hunters. They didn’t like seeing that kind of story on screen.

I wonder how such disgruntlement sounds to the non-hunting majority. Does it sound like these hunters don’t care about the wounding of animals? Does it sound like they’re trying to hide or minimize something?

It’s not as though wounding is any secret. Hunters have written entire books on how to find wounded animals. Wildlife biologists have done studies on wounding-and-loss rates. You can find discussion threads about wounding on hunting and anti-hunting websites alike.

I also wonder:

- Do hunters dislike the public dissemination of stories about wounded animals mostly because they fear it will harm hunting’s public image?

- Or does their discomfort also stem from being reminded that hunting can be messy, that it is not always the clean-killing endeavor we wish it was?

I once saw a broadhead buried in a deer’s skull. The animal apparently survived that way for a year or more.

I once heard a hunter describe a gruesome picture caught by his trail camera: a buck with leg muscles torn apart, presumably by a rifle bullet. He grimaced and shook his head. He doubted the animal would survive.

Do I like seeing such things, or hearing such stories? Hell, no. They make me queasy.

But I think it’s a good kind of queasy. It’s the kind that makes me careful.

© 2011 Tovar Cerulli

Deer: Part of every stew, every salad, every stir-fry

Venison, a forester friend tells me, is the best way he knows to eat trees. He points out that whitetails do a dandy job of converting cellulose into protein.

When Cath and I sit down to a bowl of venison stew, we are eating more than potato, carrot, and deer. We are also eating maple seedlings and cedar twigs. We are eating clover from a nearby meadow and corn from the edge of a farm field. We might even be eating hosta leaves and daylily buds from our own flower gardens.

If we lived thirty miles south of here, the whitetails—and thus we—we would be eating many more acorns.

If we lived where soy crops were common, they and we would be eating many more soybeans. (Given deer’s fondness for soy, I think it’s fair to consider Illinois venison a highly metabolized form of tofu.)

In a sense, though, the flip side is also true.

In my latter days as a vegan, I was shocked to learn how many whitetails are killed by farmers. Considering that deer were being shot to bring us tofu, how vegetarian were our stir-fries? Considering that they were even being shot to bring us greens and strawberries from the organic farm just down the road, how vegetarian were any of our meals?

I was also fascinated to learn about the role that agriculture played in the politics of early deer management.

Take Vermont, for instance: In 1897, when the state legislature allowed deer hunting for the first time in three decades, the move was made largely in response to farmers’ complaints about crop losses as the nearly exterminated whitetail began to recover. Up through 1920, the regulation of deer hunting in Vermont—for both bucks and does—was largely determined by agricultural interests and was aimed at keeping deer numbers low.

By 1920, though, hunting was becoming popular. The political tide had begun to turn and the Vermont legislature established bucks-only regulations that allowed the whitetail population to grow.

As a vegan, I could have argued that hunters themselves created the present situation—in which the successful cultivation of just about every American crop depends on killing deer. I could have pointed out that deer would still be scarce today if farmers had had their way.

But what would I have been advocating for? More intensive hunting in the past, to relieve me of a moral quandary in the present?

No matter how I sliced it, deer would always accompany me at the dinner table.

Note: I got thinking about this post after reading a recent piece by Al Cambronne, wherein I learned one more thing I didn’t want to know about the U.S. beef industry. If chicken droppings don’t strike you as a taste treat, you might not want to know either.

© 2011 Tovar Cerulli

An absence of orange (and other sins against safety)

The young man’s hunting outfit consisted of dark wool pants, a camouflage vest, and a brown knit hat just a couple shades lighter than winter deer hair. (Strike One: It was rifle season and he wasn’t wearing a stitch of blaze orange.)

His lever-action rifle, aimed downward, was pointed at the laces of his left boot. (Strike Two: He was apt to blow a hole through his own foot.)

In two minutes of conversation, I learned that he had never hunted this area before. (Strike Three: He had no idea where the nearest homes and driveways were, no idea which directions were and were not safe to fire in.)

I pointed across a wooded gully to our right and told him that our house was about a hundred yards away, beyond the safety-zone sign tacked to that maple. Then I pointed across the small beaver pond in front of us, indicating that our neighbors’ house was right there, beyond that single row of softwoods.

That was three months ago, and I still find my thoughts wandering back to that young man. In particular, I find them wandering back to Strike One.

In Vermont, as in a number of other states, it’s legal to hunt without wearing any blaze orange, even in rifle season.

But should it be?

If my libertarian-minded father was alive today, I reckon he would argue that folks should be allowed to wear whatever they want to. A New Hampshire resident, he always supported the state’s refusal to instate a motorcycle-helmet law, saying “If you’ve got a $10 head, wear a $10 helmet.” Though helmetless riders made me think that the state motto should be changed to “Live Free and Die,” I grant that my father had a point.

I grant, too, that red-and-black-checked wool jackets—the Vermont hunter’s traditional garb—have far more aesthetic charm than my neon orange vest.

And I grant that a human does not look like a deer, no matter what jacket or vest they’re wearing. No one will ever be mistaken for game by a hunter who makes absolutely certain of what he or she is shooting at.

On the other hand, not every hunter makes absolutely certain. Rare though it is, humans do sometimes get mistaken for animals. Statistically, blaze orange does a very good job of preventing such horrors. (The New York Department of Environmental Conservation, for instance, reports that 15 big game hunters were mistaken for deer or bear and killed in the state in the past decade. Not one of them was wearing orange.)

And even for the very careful hunter, I find it easy to imagine scenarios like this one: A hunter sees a deer in the woods, thirty yards off. She raises her rifle. What she does not know is that another hunter—a young man, perhaps—is stalking through woods seventy yards beyond the deer.

Does she catch a glimpse of blaze orange among the tree trunks, before squeezing the trigger? If not—and if her bullet travels a hundred yards—what becomes of him, of her, and of both their families?

© 2011 Tovar Cerulli