In college, studying Mahatma Gandhi’s moral and political philosophy, I was impressed by the twin commitments of his lifelong quest for truth.

On the one hand, he lived according to what he saw as the truth, which must, he wrote, “be my beacon, my shield and buckler.” On the other hand, he had the humility and wisdom to recognize that his truth was incomplete, that it was only “the relative truth as I have conceived it.” Closing himself off to new insights would obstruct his search.

On the one hand, he lived according to what he saw as the truth, which must, he wrote, “be my beacon, my shield and buckler.” On the other hand, he had the humility and wisdom to recognize that his truth was incomplete, that it was only “the relative truth as I have conceived it.” Closing himself off to new insights would obstruct his search.

At the time, in my early years as a vegan, I was confident I had a lockdown on dietary truth. Lacking Gandhi’s humility, it never occurred to me that someday I might have to lay down that particular shield and buckler.

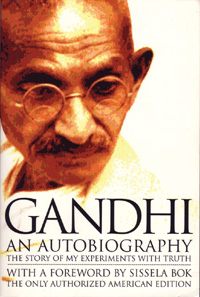

Had I paid closer attention to Gandhi’s experiments with diet, they might have been instructive. He tried eating meat in his youth, returned to the traditional Hindu and Jain vegetarian diet on which he was raised, then went vegan.

Eventually, though, recovering from an illness, he found he could not rebuild his constitution without milk. In his autobiography, he warned others—especially those who had adopted veganism as a result of his teachings—not to persist in a milk-free diet “unless they find it beneficial in every way.”

But I wasn’t ready to hear that then. Nor was I ready to hear that other great teachers of compassion—the Dalai Lama, for example—were not the vegetarians I imagined them to be.

It was only later that some faint echo of Gandhi’s wisdom tempered my certainty.

It was only when I found that my body, too, was healthier if I consumed animal products that my truth changed. It was only when I learned that the production of almost every food I ate depended on controlling cervid populations—that is, on the annual slaughter of millions of deer across North America, by hunters and farmers alike—that I began to see a bigger picture.

Now, I wonder: How would Gandhi have responded if he had found that his body, like the Dalai Lama’s, thrived on meat? What would he have done if it turned out that even the cultivation of the fruits and nuts he ate depended on the constant killing of large, charismatic, wild mammals?

© 2010 Tovar Cerulli

Kneeling beside my first deer, I had no words. I just sat there stunned, my hand on his shoulder, uncertain whether I would ever hunt again.

Kneeling beside my first deer, I had no words. I just sat there stunned, my hand on his shoulder, uncertain whether I would ever hunt again.

The timing was dead-on.

The timing was dead-on.