When the strange idea of becoming a hunter crept into the back of my mind more than a decade ago, I was hungry for guidance. I was hungry for practical advice, yes. But I was also hungry for ways of thinking.

I sensed that hunting—like gardening or forestry—could be an integral part of respectful, mindful living. I sensed that it could be a practice of re-membering: of recalling and reaffirming our membership in the larger-than-human natural world.

I was looking for expressions of hunting in this spirit.

In that quest, I talked with my uncle Mark, kept my ears sharp for meaningful conversations among other hunters, and kept an eye out for books like Heart and Blood and essays like those in A Hunter’s Heart. I was alert to anything that might help me orient myself as I stepped into the unfamiliar terrain of hunting.

I would have been intrigued then, as I am now, by the MOOC (Massive Open Online Course) the University of Wisconsin is about to launch.

You may be familiar with Leopold’s articulation of the land ethic in A Sand County Almanac: “A land ethic changes the role of Homo sapiens from conqueror of the land-community to plain member and citizen of it. It implies respect for his fellow-members, and also respect for the community as such.”

If so, then most of the course title—“The Land Ethic Reclaimed: Perceptive Hunting, Aldo Leopold, and Conservation”—probably makes sense to you. And you won’t be surprised to learn, as I recently did, that the phrase “perceptive hunting” echoes that ethic. According to the course site, it means hunting with awareness of our impacts and a grounded understanding of our participatory roles in ecological systems, “taking into account the whole system that is affected when we hunt.”

The free course is open to everyone, with an unlimited number of participants. It is especially appropriate for hunters, the hunting-curious, local food enthusiasts, and nature and science lovers of all stripes. It promises to help people understand “the historical legacy of wildlife management,” “the role of wildlife in ecosystems,” “the importance of ethics in guiding management decisions and hunter choices,” and “the emerging face of hunting today,” among other topics.

.

The course starts January 26 and runs until February 22. You can learn more at the UW MOOC site. And you can register here, as I recently did.

If you don’t have time to take the course over the next several weeks, you can do it later. The content will remain online for future access.

If you happen to live in Wisconsin, check out the upcoming special events, including two February classes on hunting and preparing wild game and an April appearance by Steve Rinella.

With hunting and conservation both in a period of rapid transition—culturally, demographically, fiscally, and otherwise—this strikes me as the perfect time to reclaim and reexamine Leopold’s land ethic. Anyone with a stake in wildlife conservation, hunting, food, or biodiversity (in other words, each and every one of us) has something to learn from, and contribute to, explorations of these matters.

Fantastic idea. I hope it’s well attended.

I hope so, too, Paul.

In the bigger picture, it’s the kind of course humanity needs to attend.

Looks interesting– I will give it a go (why not?) but I’ll also make a wager that it subscribes to the mainstream “environmental management” point of view, which reduces individual beings to mere parts of the whole (as in population ecology and conservation biology), and sees humans as properly the masterly managers of the entire system, for the maximisation of system-oriented measures. The system is what we are concerned with, and the lowest level we have any concern about is the species level. Hence, “our expanded role”, “the whole system”, “conservation management”, “conservation science”, “American conservation model”, etc.

The people running the course, like so many others, seem to equate all of this with Leopold’s position, citing this quote:

“A thing is right when it tends to preserve the integrity, stability, and beauty of the biotic community. It is wrong when it tends otherwise.”

J. Baird Callicott (who by the way has built a career on the desire to “reclaim and reexamine Leopold’s land ethic”) takes this point of view and explicitly labels the land ethic a holistic ethic, famously leading Tom Regan to brand his ethics “environmental fascism”! Of course, Regan’s ethics are just as wrong in reducing the whole to a collection of hyper-autonomous parts (with “rights”) as Callicott’s are in reducing the parts to mechanical elements of the whole.

But Regan has a point. Ecosystems are communities of beings who are having relationships with eachother. Any viewpoint that ignores that (as the conservation biology and environmental management paradigms do) is going to have a hard time being a properly ethical position, if you ask me. And Tovar I’m betting you would agree. The Mindful Carnivore is not just mindful of ecosystems at a system or population level, but also of the individual beings who are caught up in our efforts to feed ourselves.

That’s not to tar Leopold with the same brush as Callicott and environmental management. There’s another popular Leopold quote that’s relevant:

“In short, a land ethic changes the role of /Homo sapiens/ from conqueror of the land-community to plain member and citizen of it. It implies respect for his fellow-members and also respect for the community as such.”

The second sentence is often left out when people quote this, but it’s crucial. Here we see an ethics framed that pays attention to the individuals as well as the community. Moreover it eschews anthropocentrism in favour of ecological egalitarianism and it “situates humans ecologically, and nonhumans ethically” (Val Plumwood’s great summation of the task of cultural remaking needed to end the ecological crisis.)

To me, in that quote (much more so than “A thing is right…”) is a great nugget of wisdom that can be used to navigate this great schism that exists, not just between conservationists and animal rightsists, or Callicott and Regan, but more relevant for us, between “utilitarian/meat hunters” (to borrow Kellert’s term) and anti-hunters, between redneck and greenie. The middle way of this quote is the way I take; it is the only way that is compatible with a genuinely ecological outlook, and for this reason is common to so many indigenous cultures, and, I thought, was what The Mindful Carnivore was about, too!

Thanks very much for your insights, Russell. Thanks, too, for your generous appraisal of my book and the ground I cover there.

You win your bet. I think your critiques (and Plumwood’s) are on the mark. And that, of course, is the very Leopold quote I opted to use in defining the land ethic above.

As you suggest, people often argue that animal-rights advocates care only about individual animals while conservationists (including hunter-conservationists) care only about populations. Though there is some truth to that, I think both characterizations are a bit overblown. They may be accurate in describing schools of thought, but they often break down rather quickly when we attend to individual people’s perceptions and values. For many individual hunters, for instance, the “clean kill” ethic is evidently rooted in concern for individual animals and their potential suffering.

I wonder how Leopold’s vision — and his articulation of it — would have evolved if he had lived longer. His understandings and attitudes shifted dramatically between his late 20s and his late 50s. Who knows how he would have been thinking by his late 70s or 80s?

Nature itself reduces individuals to parts of the whole – at best. Nature couldn’t care less about individuals living miserable lives or dying hideous deaths.

I am uncomfortable with the degree of management humans undertake, our decision-making for all the other species, but short of a virus wiping out humanity – which is certainly a possibility and wouldn’t be the worst thing to happen to the planet – it is like democracy: a crappy system, but better than the alternatives.

Thanks for the tip about the course, Tovar – sounds interesting.

Hmm, I have just written then snipped a big long diatribe :).

Holly, I guess I’d just say, nature creates and sustains every living individual. That’s a pretty big gift to receive from a party who “couldn’t care less”. We might not like certain aspects of their design — suffering and death — but we can’t deny they are essential. Is our life only worth living since we have attempted to extract ourselves to some degree from nature’s systems of torture and slavery to the good of the whole? I think most indigenous cultures, who haven’t taken our Western path of trying to pull ourselves out of nature, would disagree. Strongly.

Well Russell, I’m sorry your response disappeared, but I should clarify a couple things:

I very much care about individual lives. I rescue worms that get stuck on sidewalks after a rain, pull spiders from the bathtub before I turn on the water and rail against any killing that is done solely for amusement. And I hunt for the meat I eat.

I also think our departure from the hunter-gatherer lifestyle is the biggest mistake we’ve ever made. But that genie is out of the bottle and the fact is that we have bolloxed things up pretty good since then. So now we’re in a system where we have to manage wildlife and wild places in order to mitigate our impacts on them, supplanting what nature used to do. And what nature used to do (and still does, in some places) is regulate systems and populations with utter indifference to individuals.

Of all the crappy things humans have done to wildlife, managing them with the same indifference to individuals as nature is the least of my concerns. In my individual actions, I will remain respectful of individual animals, but I don’t believe large-scale management can or should do the same. I’d rather spend my limited surplus energy helping people discover healthy and more respectful alternatives to the disastrously cheap meat that comes from factory farms.

All good Holly – it sounds like we’re on the same page!

Holly, I was thinking some more today as to what issue you might have had with what I wrote, and it occurred to me my comment could easily be seen as an attack on wildlife management itself.

I should have clarified, what I’m actually taking issue with is the mentality that hunting is *all* about conduct in those higher-level impersonal domains addressed by conservation science. If a hunter thinks what she/he is doing is nothing personal, just “managing the herd”, or “filling the freezer”, to me yes this is a problem — not necessarily a *big* problem, if the hunter still *acts* like someone who cares about the animal as person by virtue of following socially-ingrained moral codes that demand swift kills, following up wounded game, etc, but still, I think if anyone thinks that the population level and above is the only thing that matters, they are wrong, and also, they are wrong if they try to equate Leopold’s land ethic with that position. I suspect this is what the course we are discussing is about to do, but with any luck I will soon be proven wrong!

(The other issue that ties into this for me is that I think, especially here in Australia, there is a tendency to, really embarrassingly transparently, pretend that selfless, conservation wildlife management – of ferals, in our case – is the main motivator for hunters. Our real primary motivations, to feed ourselves in an ecological manner, with a proper degree of emotional engagement with our quarry, are perfectly compatible with ecological ethics and perfectly defensible against the attacks of the antis. Why hide behind an obvious bit of spin when you could just stand up and speak the truth? )

Oh, that clarification does help. I agree. I don’t believe for a second that anyone hunts for conservation/management, though sometimes management is a key benefit of what we do.

I think people say that because 1) they don’t distinguish between benefits and motivations and 2) it’s easier than admitting that hunting brings us joy, which is the primary reason I think most of us do it, and something that’s very hard to explain to non-hunters.

For me, food is a primary motivation – I will absolutely not point my gun at anything I don’t intend to eat, and it was feasting on fat wild ducks that clinched my decision to start hunting nine years ago. But that wouldn’t be enough if I didn’t love the act of hunting. If hunting was a mere utilitarian act of feeding myself, I could raise fatter animals humanely in my back yard and spend far less money on the act of killing.

Now, joy, love of eating the animals I hunt and loving the animals I hunt are all so closely entwined that I can’t separate them at all. I don’t apologize for it, but I do spend as much time as I can explaining it.

Excellent, Holly, I had a feeling we were on the same page ! Totally agree and with regards to the last sentence, I try to do the same thing myself.

“I will absolutely not point my gun at anything I don’t intend to eat” raises an interesting issue. I feel the same way. On the other had we have huge ecological problems with feral cats and foxes here in Australia. Like you, I don’t want to kill them if I’m not going to eat them, and I don’t fancy eating cat or fox so I won’t do it – but someone unfortunately needs to kill them, for the good of native ecosystems and their members. A vexed issue.

Excellent discourse, Russell and Holly. Thanks for that.

“I will absolutely not point my gun at anything I don’t intend to eat” raises an interesting issue.” …

It sure does. I could tell a number of stories along this vein. But I’ll share one:

I have a very sensitive neighbor who comes pretty close to qualifying as an “anti”, without the affiliations or activism. We met in the woods years ago and she seemed affronted that a stranger (me) was in “her woods” (isolated public land backing hers). That initial conversation ended with her saying that she saw herself as a “protector of the forest”. I replied that I too considered myself as such. In the years since we have grown to respect each other greatly, becoming friends as well as neighbors. We keep each other up on wildlife sightings and occasionally one of us would call the other on the phone blurting out, “Guess what I just saw!” It was a number of years before I told her I hunted.

Just a few years ago we were talking about new, and invasive, species in our area following a large forest fire and I told her I had taken to shooting the starlings around my home. They were competing directly with the bluebirds (mountain and western) and woodpeckers. At one point, I’d actually had a flicker and starling tumble from a cavity to the ground at my feet, locked in battle. I used .22 match grade CB rounds that produce a muffled report, akin to a stick breaking, and I removed 3 or 4 pairs of starlings each spring.

Then came the cowbirds –parasitic nesters whose numbers had increased alarmingly post-fire. Although it can be argued that cowbirds are native and fires are “natural”, the catastrophic burn that ensued after decades of human fire suppression resulted in a post-fire landscape that looked as much like prairie as “mountain meadow”. Debates rage about cowbirds and, following, just what exactly is “natural” anymore. My own decision was to let the cowbirds be.

I had shared these ramblings with my neighbor and she appreciated the dilemma. She has various cavity nest boxes throughout her property too. Then we each got a pair of post-fire kestrels, and we were both elated. We each set out folding chairs within binocular range of our respective cavities and kept each other informed of how many voles and grasshoppers the parents brought in, and how many chicks we thought we were inside. Interestingly –especially if you are a hunter too– the voles were caught only at low light -crepuscularly and on overcast days. I watched “my pair” fledge 5 beautiful young kestrels.

Then came the magpies. They’d had a banner year and I counted 30 in the flock that had descended on my meadow that summer. They harassed the fledgling kestrels mercilessly and pirated the adults when they came in with food. My neighbor called almost distraught, worried that the magpies would result in the death of her young kestrels. She then stunned me by asking, “Would you be willing to come over and shoot them?”

I told her no. She understood completely but hung up in tears. Strange animals we are.

Oh yes… that same year we also discovered the downright viciousness of house wrens. Those cute little feathered ping-pong balls with the merry bubbling song will attack a nest box full of bluebird chicks by pitching them out onto the ground one by one. I overruled this perniciousness only to be trumped by the wren’s next tact –to stuff the nest box full with twigs, piled over the top of the bluebird nestlings. The nestlings expired before I discovered it. Parent bluebirds apparently aren’t equipped to deal with the aggressive territorial tactics of wrens. Guess it was my fault placing that nest box too close to an aspen grove. Live and learn?

It sounds like an interesting course Tovar. I will be sure to check out the content online to see how it goes.

It sounded from the youtube as if they wouldn’t be looking closely at Sir Aldo’s exact suggestions for Game Management, indeed they make no reference to that 450 page book he wrote in his mid 40s, which is a shame. The Preface he wrote to Game Management was as inspirational as anything I’ve ever read, and if Sand County can be considered a motivational text, Game Management is the nuts and bolts blue print of how to get it done. Any discussion of Leopold and hunting is the worse for passing it over.

Recently Leopolds entire archives of written correspondence and photos have become available online via the University of Wisconsin. They are not transcribed and so must be read in the original. I spent a couple nights reading mostly Aldo’s side of his correspondence with his son Starker (Aldo Starker Leopold) who was a conservationist in his own right. Aldo typed, and kept copies of most letters he sent so they are easier to read than the longhand script he received in reply. The personal as well as professional communications from father to son are illuminating. Besides all that those two just loved to hunt. 🙂

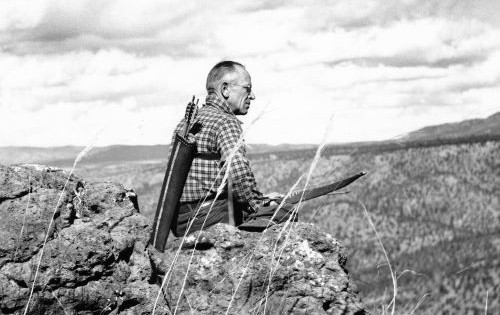

One of my favorite photos from the archive is Starker in 48 with certain Mexican subspecies he took on a long planned and discussed hunt in Mexico. The physical similarities between father and son are striking.

What do folks hunt in Vermont in the winter?

I’m not sure about the details of the course content, Robb. Given that it’s only supposed to take a couple hours a week for just a few weeks, I imagine the volume of materials won’t be huge.

I haven’t looked through the correspondence archive, but it sounds fascinating. Starker certainly made his mark, including the part he played in drafting Missouri’s “Design for Conservation” and helping the state secure sales-tax support for fish, wildlife, forestry, parks, etc.

Here in Vermont, there’s a rabbit/hare season that runs until early March. But hunting participation is a lot lower than in the autumn deer seasons. It’s even lower for other winter seasons (e.g., furbearers).