I disposed of the lead fragment and picked through the rest of the venison carefully. I hoped none of my bullets would ever come apart like that again.

Tag: unintended harm

Porcupines, plywood, and interspecies peace

Last summer, when a mother bear and three cubs raided our apple trees at dawn, Cath and I watched, spellbound. Some broken branches and a few dozen apples were no great loss—nothing compared to the privilege of watching bruins in our front yard.

In winter, when red squirrels pilfered sunflower seeds from the bird feeders, we watched again. When I chased them off, it was merely to give the finches and chickadees a turn.

I like living peaceably with my fellow creatures. I begrudge them little.

The main exception to that peace is my hunting. A few weeks each year, I set off into the woods with bow or gun. Most of that time, I’m still watching in quiet admiration. I may not get (or take) the chance to kill. If I do, it is for food, not spite.

Lately, though—reflecting on some of the responses to one of Holly’s recent posts over at NorCal Cazadora—I’ve been thinking about other, less-frequent exceptions to my gentle interspecies relationships.

I’ve been thinking, for instance, of the three or four woodchucks that have burrowed in deep under our garden fence in the past twelve years. I killed them reluctantly, again for food: for the green beans and broccoli my furry friends were happily gorging on, and sometimes for their meat, too.

Less comfortably, I’ve been thinking about porcupines.

I have nothing against our spiny neighbors and enjoy seeing them in the woods. The harm they inflict on our apple trees is minor. The damage they do to building materials (whether part of our house, or tucked under our shed) is usually tolerable. The risk they pose to our black Lab, Kaia, is minimal; between her sense of caution and my calling her off, she has never made full contact.

Some years ago, however, things went too far.

It wasn’t any one thing.

It wasn’t just that two porcupines had been visiting nightly for weeks and that Kaia finally got quilled, in broad daylight, no less: one paw bristling with forty small, black needles.

It wasn’t just that the porcies, attracted to the resins in laminated wood, had finally gnawed right through the back corner of the plywood doghouse under the front porch, and were making more frequent forays up onto the porch to gnaw at certain spots on the decking (something salty spilled there years ago?), on the siding next to the front door (something special in the stain used there?) and on one of the 4×4 posts that hold up the porch roof (who knows?). One night they sampled a pair of rubber boots.

It wasn’t just that they were keeping us awake in the middle of the night, with chortling conversations in the trees just outside our bedroom window, or with sounds of their gnawing reverberating through the framing of the house. Yelling and throwing pebbles drove them away only briefly.

It wasn’t just that I had seen them around our vehicles of late, reminding me how they had nibbled through a brake hose a few years earlier: a problem I discovered on the way to work the next morning, when my foot went to the floor without slowing my pickup at all. I was grateful for a long driveway and a hand brake. The truck—our only vehicle at the time—was out of commission for three days while a replacement hose was located.

It was all those things added together.

Finally, late one night, wishing we had a few more fishers around, I suppressed my neighborly instincts and shot both porcupines.

Hating the killing, I told myself that I should cook them up as Bob Kimber describes doing in Living Wild and Domestic. But, in the middle of the night, I didn’t have the oomph to try butchering my first porcupines. So, with apologies, I slung them into five-gallon buckets and took them deep into the woods where no dog would find them.

Late the next night, I woke and heard noises. Not porcupine noises, surely.

Yes, porcupine noises. Groaning, I steeled myself, rolled out of bed, and went to fetch the .22.

By week’s end—surprised both by their numbers and by my knack for the dubious skill of holding both rifle and spotlight—I had killed six or seven.

I was not a hunter those nights. I was an executioner, disposing of fellow creatures whose only crimes were a burgeoning population, a territory that overlapped with ours, and a few unfortunate gustatory preferences.

I can think of only one upside to that grisly week. It worked. Though porcupines still abounded in the woods, they stopped trying to dismantle our house.

Relieved, I put away my black hood.

© 2010 Tovar Cerulli

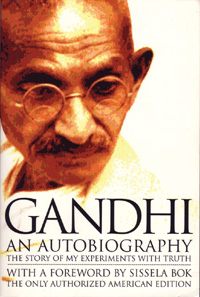

Hunting with Gandhi

In college, studying Mahatma Gandhi’s moral and political philosophy, I was impressed by the twin commitments of his lifelong quest for truth.

On the one hand, he lived according to what he saw as the truth, which must, he wrote, “be my beacon, my shield and buckler.” On the other hand, he had the humility and wisdom to recognize that his truth was incomplete, that it was only “the relative truth as I have conceived it.” Closing himself off to new insights would obstruct his search.

On the one hand, he lived according to what he saw as the truth, which must, he wrote, “be my beacon, my shield and buckler.” On the other hand, he had the humility and wisdom to recognize that his truth was incomplete, that it was only “the relative truth as I have conceived it.” Closing himself off to new insights would obstruct his search.

At the time, in my early years as a vegan, I was confident I had a lockdown on dietary truth. Lacking Gandhi’s humility, it never occurred to me that someday I might have to lay down that particular shield and buckler.

Had I paid closer attention to Gandhi’s experiments with diet, they might have been instructive. He tried eating meat in his youth, returned to the traditional Hindu and Jain vegetarian diet on which he was raised, then went vegan.

Eventually, though, recovering from an illness, he found he could not rebuild his constitution without milk. In his autobiography, he warned others—especially those who had adopted veganism as a result of his teachings—not to persist in a milk-free diet “unless they find it beneficial in every way.”

But I wasn’t ready to hear that then. Nor was I ready to hear that other great teachers of compassion—the Dalai Lama, for example—were not the vegetarians I imagined them to be.

It was only later that some faint echo of Gandhi’s wisdom tempered my certainty.

It was only when I found that my body, too, was healthier if I consumed animal products that my truth changed. It was only when I learned that the production of almost every food I ate depended on controlling cervid populations—that is, on the annual slaughter of millions of deer across North America, by hunters and farmers alike—that I began to see a bigger picture.

Now, I wonder: How would Gandhi have responded if he had found that his body, like the Dalai Lama’s, thrived on meat? What would he have done if it turned out that even the cultivation of the fruits and nuts he ate depended on the constant killing of large, charismatic, wild mammals?

© 2010 Tovar Cerulli

Ceremony for a meal

Kneeling beside my first deer, I had no words. I just sat there stunned, my hand on his shoulder, uncertain whether I would ever hunt again.

Kneeling beside my first deer, I had no words. I just sat there stunned, my hand on his shoulder, uncertain whether I would ever hunt again.

Finally, I whispered something clumsy: half gratitude, half apology.

The next year, when my second deer dropped in his tracks, I was shaken but less shocked. I spoke my thanks and asked forgiveness simply, without grace.

It was after my third deer fell that I knelt to lean a few small sticks against each other, then cloaked them with three fern fronds, still green in mid-November.

If I had grown up in a family of hunters, or in a culture that spoke to the wild, perhaps I would have had some prayer or ceremony at the ready. As it is, the words and gestures are still part of what I hunt for. Over time, as I find them, perhaps a ritual habit will take root in the thin soil of my few years afield.

These gestures need not be confined to the hunt, of course.

Considering all the deaths we inflict, directly and indirectly, there’s as much reason to fall to my knees by a shelf full of bread or corn chips in the grocery store, or even by a display of organic produce at the local farmers’ market.

Yet, standing in front of fruits and vegetables grown by others, I have the luxury of not knowing what cost they incurred.

Maybe the harm was no worse than the initial “conversion” of forest to tillable farm land, plus a few earthworms chopped by shovel or tractor, or some caterpillars knocked off by a bacterial insecticide.

Considering the larger impacts I know my life has, I have decided not to worry about individual invertebrate deaths. I value them ecologically and gently escort many insects out of our house. But I crush the cucumber beetles that attack our squash seedlings.

On the other hand, maybe a few toads were diced in the tilling. Maybe the field was fertilized with compost made from both the manure and the carcasses of cows. Maybe the bushels of greens on display at the farmers’ market took the life of a family of woodchucks. Maybe the flats of strawberries grew to ripeness thanks to the killing of a deer or two.

A long list of maybes: things most of us don’t know or care to know.

When I garden—uprooting weeds, mashing beetles, occasionally shooting a woodchuck—the luxury of ignorance begins to fade.

When I kneel beside a dead whitetail, it disintegrates. Yanked out of forgetfulness, I find I must offer some gesture of gratitude and apology, no matter how clumsy.

© 2010 Tovar Cerulli

‘I could definitely kill one of those’

The timing was dead-on.

The timing was dead-on.

Just as I walked past the table, the woman said, “My rule is, ‘I’ll only eat it if I could kill it.’ And I could definitely kill one of those.”

I left the restaurant chuckling. I was thinking how the line echoed one of my reasons for taking up hunting: to face the killing of the fellow vertebrates I had begun eating after a decade of abstention. There would, I felt, be a lesson in that confrontation.

But the line also reminded me how complex our eating is.

As a vegan, my rule had been like hers. I was unwilling to kill animals or keep them penned up—or to have someone else do the killing or penning for me—so I didn’t eat their flesh or even their eggs or milk. I was okay with the killing of vegetables, grains, and legumes. Whether I grew it myself or bought it, the question seemed simple: Was I willing to behead broccoli?

Eventually, though, I came to the uncomfortable realization that harvesting individual plants was not all it took to put vegetarian meals on my plate.

- Was I willing to remove wild plants (trees, grasses, and wildflowers) from a given area, to make room for domesticated plants? Was I willing to evict the wild mammals, birds, reptiles, and amphibians who lived there?

- Was I willing to keep marauding insects and herbivores at bay? If deterrents and repellents didn’t work—if fences were breached or unaffordable—was I willing to kill beetles, woodchucks, and deer so I could eat?

- If not, was I willing to do all of the above by proxy, knowing someone else had done it for me?

Faced with these questions, I had to (A) stop eating, (B) stick my head back in the sand, or (C) make peace with a far more complex picture of what it meant to be alive. I opted for C.

Yet I do still find value in posing the woman’s simpler question, especially when I’m about to eat flesh: Could I kill one of those?

And I still find myself wishing I had seen what was on her plate.

© 2010 Tovar Cerulli

Kinds of harm

The doe stepped into the road, then trotted across and bounded into the woods as I slowed the car. Cath and I both relaxed. We weren’t going fast, but that had been close.

Then the second doe was there, very close, pausing at the edge of the road. I caught the flash of movement at the periphery of the headlights as she leapt forward. I went hard left. But she came fast. Cath and I heard the bodily thud as she careened off the passenger side.

I stopped and backed up. The doe was lying in the road. Done for, I thought. Then she raised her head. Oh, no. A sick feeling rose up inside. Done for, but not dead. I’d never hit a deer before. And I was going to have to finish this one off, which would be illegal—or drive the half-mile back home, call a game warden, and make the doe wait for mercy at the official hand of the law.

When Cath and I got out of the car, the doe stood up. Then, recognizing us as bipeds, she trotted off and disappeared into the woods. Looking at the dented fender over the wheel, we realized it was more a case of deer-hitting-car than car-hitting-deer.

As we drove off, we talked about it. We agreed that we’d been lucky. It could have been far worse: for us, the doe, and the car.

Three hours later, I followed the doe’s tracks by flashlight, figuring she’d stop nearby if she was seriously hurt. I found only tracks; no sign of a fresh bed. Imagining her chances were good, I prayed she’d make it with nothing more than bruises and a newfound respect for headlights.

But the incident still troubled me.

It wasn’t news to me, of course, that animals get maimed and killed by cars. As a volunteer firefighter, I’d been on accident scenes. I’d led wardens to mortally wounded deer and heard the gun’s sharp report. Nor was it news that we maim and kill in all kinds of other ways, incurring a massive debt in animal lives and, worse, in habitat. But it’s easy to forget these things, to put them comfortably out of mind. And I’d always found such harm—regrettable, but unintended—easier to accept than premeditated killing.

The doe challenged me to reconsider that.

Just five weeks before she leapt at our car, I’d put a bullet through another deer’s heart. The buck had collapsed in moments; no time for shock to turn into pain. As deer kills always do, that one had shaken me with its reverberations.

But the doe, and the sick feeling that rose up as I saw her lying there in the road, made me ask: Do I really find it easier to accept the inadvertent, often-messy, often-unseen ravages I inflict on my fellow creatures?

The answer, I find, is no. Assuming it’s done quickly, I’m more at peace with intentional harm. With the kill I’ve prepared for and chosen.

© 2010 Tovar Cerulli