Months ago, I was going to write about making my first drum.

Tag: traditions

A hunting culture in decline: Causes and consequences

We conserve and protect what we care about. If we don’t care much, where in our hearts can a serious conservation ethic possibly take root?

The ‘sport’ of hunting: Why I don’t call it that

In a world like ours, where discussions of hunting are already full of pitfalls and confusions, “sport” and “recreation” only get in the way.

An absence of orange (and other sins against safety)

The young man’s hunting outfit consisted of dark wool pants, a camouflage vest, and a brown knit hat just a couple shades lighter than winter deer hair. (Strike One: It was rifle season and he wasn’t wearing a stitch of blaze orange.)

His lever-action rifle, aimed downward, was pointed at the laces of his left boot. (Strike Two: He was apt to blow a hole through his own foot.)

In two minutes of conversation, I learned that he had never hunted this area before. (Strike Three: He had no idea where the nearest homes and driveways were, no idea which directions were and were not safe to fire in.)

I pointed across a wooded gully to our right and told him that our house was about a hundred yards away, beyond the safety-zone sign tacked to that maple. Then I pointed across the small beaver pond in front of us, indicating that our neighbors’ house was right there, beyond that single row of softwoods.

That was three months ago, and I still find my thoughts wandering back to that young man. In particular, I find them wandering back to Strike One.

In Vermont, as in a number of other states, it’s legal to hunt without wearing any blaze orange, even in rifle season.

But should it be?

If my libertarian-minded father was alive today, I reckon he would argue that folks should be allowed to wear whatever they want to. A New Hampshire resident, he always supported the state’s refusal to instate a motorcycle-helmet law, saying “If you’ve got a $10 head, wear a $10 helmet.” Though helmetless riders made me think that the state motto should be changed to “Live Free and Die,” I grant that my father had a point.

I grant, too, that red-and-black-checked wool jackets—the Vermont hunter’s traditional garb—have far more aesthetic charm than my neon orange vest.

And I grant that a human does not look like a deer, no matter what jacket or vest they’re wearing. No one will ever be mistaken for game by a hunter who makes absolutely certain of what he or she is shooting at.

On the other hand, not every hunter makes absolutely certain. Rare though it is, humans do sometimes get mistaken for animals. Statistically, blaze orange does a very good job of preventing such horrors. (The New York Department of Environmental Conservation, for instance, reports that 15 big game hunters were mistaken for deer or bear and killed in the state in the past decade. Not one of them was wearing orange.)

And even for the very careful hunter, I find it easy to imagine scenarios like this one: A hunter sees a deer in the woods, thirty yards off. She raises her rifle. What she does not know is that another hunter—a young man, perhaps—is stalking through woods seventy yards beyond the deer.

Does she catch a glimpse of blaze orange among the tree trunks, before squeezing the trigger? If not—and if her bullet travels a hundred yards—what becomes of him, of her, and of both their families?

© 2011 Tovar Cerulli

Mother Nature’s Child (or Girl the Hunter)

Even before the film started, my antennae were up.

Even before the film started, my antennae were up.

Cath and I had gone to the January 25th screening of Mother Nature’s Child: Growing Outdoors in the Media Age out of general curiosity. The documentary’s message would, I expected, be much like that presented by Richard Louv’s compelling book Last Child in the Woods.

In her brief remarks before the lights went down, however, filmmaker Camilla Rockwell had piqued a more specific interest. She said that certain parts of the film were “edgy.” She would be curious to hear how people felt about them.

What would be “edgy” in a documentary about connecting kids to nature?

My gut gave one answer: hunting.

In Louv’s book, I recalled, several pages were devoted to “The Case for Fishing and Hunting.” Louv wrote that these activities “remain among the last ways that the young learn of the mystery and moral complexity of nature in a way that no videotape can convey.” As a non-hunting angler, though, his focus was on fishing. Hunting remained in the background.

In Louv’s book, I recalled, several pages were devoted to “The Case for Fishing and Hunting.” Louv wrote that these activities “remain among the last ways that the young learn of the mystery and moral complexity of nature in a way that no videotape can convey.” As a non-hunting angler, though, his focus was on fishing. Hunting remained in the background.

Settling into my seat, I enjoyed the first half of the film. It’s a well-crafted piece, blending footage of young people outdoors with excerpts from interviews with adults. We saw suburban kids running through the woods and crawling through hollow logs, their voices high with excitement. We saw urban teenagers planting gardens and learning to fly-fish. We heard from teachers, parents, and researchers.

Watching and listening, I was reminded just how crucial interaction with the natural world is for children’s physical, emotional, mental, and spiritual health. I wondered, not for the first time, who I would be today if I had not spent my boyhood summers almost entirely outdoors, wandering the woods, fishing for brook trout, catching tadpoles and bullfrogs.

And then, halfway through the film, there she was: a girl about ten years old, headed to the Vermont woods with her grandfather—in blaze orange.

Sitting there in the Montpelier’s independent theater, The Savoy, we watched the girl handling a rifle. We watched her waiting in the woods. We saw clips from interviews: Nancy Bell of The Conservation Fund talking about her respect for animals and why she hunts, Jon Young talking about how close contact with nature helps young people confront deep questions concerning life and death. Finally, we saw a still image of girl and grandfather. Beside them hung a dead deer: her first.

Fifteen years ago, I would have been horrified. Killing animals, I would have argued, has nothing to do with encouraging healthy relationships with nature, especially for kids.

Now, I see it differently. The filmmakers—both of them non-hunters—have given us a fine documentary about children’s relationships with the natural world. They have also given us a stereotype buster: women and girls hunt, and environmentalists, too! Perhaps most importantly, they have given us a great conversation starter.

The film opens a door for hunters and non-hunters to talk about hunting. Why do some of us hunt? What is it about hunting that others find revolting? Is it helpful to distinguish between stereotypes and first-hand experiences? Is it helpful for non-hunters to hear from actual hunters about how they relate to nature and animals? And, of course: What roles can or should hunting play in young people’s lives?

The film also opens a door for hunters and non-hunters to talk about our shared love of nature. It’s high time, after all, that conservationists—hunters, non-hunters, and anti-hunters—stopped lobbing political firebombs at each other.

It’s time we heeded the warning issued by Richard Nelson in his introduction to A Hunter’s Heart: “After we’ve lost a natural place, it’s gone for everyone—hikers, campers, boaters, bicyclists, animal watchers, fishers, hunters, and wildlife—a complete and absolutely democratic tragedy of emptiness.” Unless we work together, how can we insure that there will be natural places left for our children to relate to?

In the post-screening discussion, it so happens, not one person drew attention to the segment on hunting.

No, I take that back. One person did, indirectly. A man stood up to say that his young son, who appeared in the film, has now taken hunter safety and has put both squirrel and rabbit on the family dinner table. The father—a non-hunter (so far)—made it clear: connections with nature, including hunting, have done the boy nothing but good.

Notes: If you know of film festivals, schools, or outdoor education centers that might be interested in showing the film (or buying the DVD), please mention it to them. If you happen to live near any of these upcoming screenings, check it out in person:

- 3/17 – Vermont Institute of Natural Science, Quechee, VT

- 3/24 – CT Outdoor & Environ. Educ. Assn Conference, New Britain, CT

- 3/25 – Environmental Film Festival, Washington, DC

- 3/26 – Green Mountain Film Festival, Montpelier, VT

- 4/5 – Springfield Conservation Nature Center, Springfield, MO

- 5/18 – Shelburne Farms, Shelburne, VT

To learn more about Richard Louv’s work, visit the Children & Nature Network.

© 2011 Tovar Cerulli

Unposted: Hunting, neighborliness, and private land

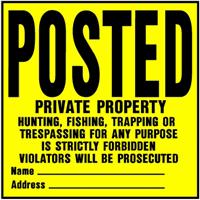

When Cath and I moved to our home here in the hills on the eastern side of the Winooski Valley, there was one group of people I wanted to keep off our few acres: hunters.

When Cath and I moved to our home here in the hills on the eastern side of the Winooski Valley, there was one group of people I wanted to keep off our few acres: hunters.

Anywhere you stood on our land—or fired a rifle—you were within a few hundred yards of our house. In most spots, you were a lot closer than that.

Our driveway is part of an old railroad bed, long used as a trail by hunters, hikers, bicyclists, cross-country skiers, and snowmobilers. Decades ago, after part of the railbed embankment washed out and disappeared downstream, a trail detour was put in around our house and driveway.

That detour winds through our woods just seventy yards from the back porch.

With safety in mind, and not liking the idea of hunting much, I did the obvious thing. I bought a roll of those ubiquitous bright yellow signs. Several went alongside the trail detour: not blocking it, but telling folks to stick to it.

Six years later, I started hunting.

Our few acres, though convenient, offered little opportunity. And, anywhere I stood—or fired a rifle—I was close to the driveway, the house, a neighbor’s house, or the frequently used trail. State land offered greater opportunity and safety, if I drove some distance to reach it. But the most convenient combination of opportunity and safety was offered by the hundreds of acres of timberland stretching out behind our house: others’ private property.

So I asked permission to hunt there.

Landowners who had grown up elsewhere thanked me for asking, and said yes.

Landowners who had grown up here were baffled by my question. Their land wasn’t posted. Didn’t I know that meant I could hunt it? (I did. The liberty to hunt on un-posted, un-enclosed private land was inscribed in Vermont’s Constitution two centuries ago.)

Talking with these landowners, I got thinking about our yellow signs.

I didn’t want to tempt fate by removing them entirely. In the previous few years, careless hunters had killed two bystanders in Vermont: one man picking berries where a hunter expected to see a bear, and another sitting in his living room watching television a long way from where a hunter missed a deer.

I didn’t want to tempt fate by removing them entirely. In the previous few years, careless hunters had killed two bystanders in Vermont: one man picking berries where a hunter expected to see a bear, and another sitting in his living room watching television a long way from where a hunter missed a deer.

Reading those stories in the newspaper, I found little consolation in the statistical fact that hunting-related injuries to humans are (1) very rare and (2) almost always self-inflicted or inflicted on another hunter.

Hunters still needed to know that our few acres were not a place for shooting.

That message, though, could take a different tone.

© 2010 Tovar Cerulli

Hunting with Gandhi

In college, studying Mahatma Gandhi’s moral and political philosophy, I was impressed by the twin commitments of his lifelong quest for truth.

On the one hand, he lived according to what he saw as the truth, which must, he wrote, “be my beacon, my shield and buckler.” On the other hand, he had the humility and wisdom to recognize that his truth was incomplete, that it was only “the relative truth as I have conceived it.” Closing himself off to new insights would obstruct his search.

On the one hand, he lived according to what he saw as the truth, which must, he wrote, “be my beacon, my shield and buckler.” On the other hand, he had the humility and wisdom to recognize that his truth was incomplete, that it was only “the relative truth as I have conceived it.” Closing himself off to new insights would obstruct his search.

At the time, in my early years as a vegan, I was confident I had a lockdown on dietary truth. Lacking Gandhi’s humility, it never occurred to me that someday I might have to lay down that particular shield and buckler.

Had I paid closer attention to Gandhi’s experiments with diet, they might have been instructive. He tried eating meat in his youth, returned to the traditional Hindu and Jain vegetarian diet on which he was raised, then went vegan.

Eventually, though, recovering from an illness, he found he could not rebuild his constitution without milk. In his autobiography, he warned others—especially those who had adopted veganism as a result of his teachings—not to persist in a milk-free diet “unless they find it beneficial in every way.”

But I wasn’t ready to hear that then. Nor was I ready to hear that other great teachers of compassion—the Dalai Lama, for example—were not the vegetarians I imagined them to be.

It was only later that some faint echo of Gandhi’s wisdom tempered my certainty.

It was only when I found that my body, too, was healthier if I consumed animal products that my truth changed. It was only when I learned that the production of almost every food I ate depended on controlling cervid populations—that is, on the annual slaughter of millions of deer across North America, by hunters and farmers alike—that I began to see a bigger picture.

Now, I wonder: How would Gandhi have responded if he had found that his body, like the Dalai Lama’s, thrived on meat? What would he have done if it turned out that even the cultivation of the fruits and nuts he ate depended on the constant killing of large, charismatic, wild mammals?

© 2010 Tovar Cerulli