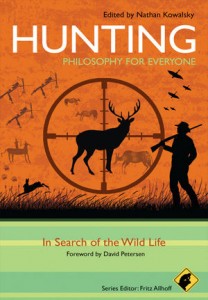

Don’t try too hard, some folks say. Desperation can drive the deer away. The less you expect, the more animals you see.

Don’t try too hard, some folks say. Desperation can drive the deer away. The less you expect, the more animals you see.

How this philosophy dovetails with the undeniable value of perseverance, I’m not sure. But there may be something to it.

In my first few years as a hunter, I dragged home exactly zero pounds of venison. It was only in my fourth autumn—after I gave up on getting a deer and decided to focus on just enjoying my time in the woods—that my first buck came along.

The next year, I had no expectation of repeated success so soon. Yet a deer came. The year after that, with less time to hunt, my expectations were even lower. Again, a deer came.

There are limits to such luck, however.

This fall, I would be too busy to spend much time in the woods. (Of late, I’ve been too busy even to spend much time in the wilds of the internet. As fellow bloggers can attest, my forays there have left few traces in the form of comments.) I felt sure our freezer would hold no venison this winter. But I promised myself I would get out for a few mornings, just to feel the forest wake at dawn.

A week ago, on opening morning of rifle season, I was doing just that. I had reached the woods a full hour before sunrise: half an hour before legal shooting light.

In the dark, I heard one deer somewhere behind me, its hooves crunching leaves. But its meandering, start-and-stop movements sounded more like a doe browsing than a buck seeking a mate. Here in Vermont, only the latter are legal game in rifle season. Slowly, the animal wandered out of earshot. Probably the only deer I would hear that morning.

No matter. My aim, as meditation teachers say, was to “just sit.” And, as woodland deer hunters say when the leaves are that dry and frosty, to “just listen.”

The rustle of a leaf.

The swishing of wings, as a pileated woodpecker moved from one tree to another.

The sounds of the forest breathing.

I can’t recall ever taking so much pleasure in simply sitting, eyes closed. My mind went still, letting go of its churning thoughts about the next chapter I would be drafting for my book, or about the research I’m doing in grad school, interviewing hunters who came to the pursuit as adults. I was hardly even thinking about deer.

I had been there an hour, listening, when the hoof steps came, moving not into the faint breeze, but with it, so that the animal’s scent was carried my way, rather than vice versa. Again, the sounds stopped and started.

A doe, I thought, maybe the same one.

But when the deer stepped into view, just ten yards off to my right and behind me, I saw antler. And—more surprising—I made out a pair of points on one side. A legal buck.

I saw, too, why the animal’s movements sounded sporadic. The buck was so hopped up on rut-time hormones that he could hardly take a step without stopping to hook a sapling with his antlers or to paw at the earth.

A few more steps, as the buck crossed behind me. An ambling turn that would take him away, yet gave me the chance to raise my rifle unseen. A clear view as he angled off. A moment’s pressure on the trigger.

Crouching beside him, I offered thanks and apology—poor compensation for what I had taken—and thought how strange this brief hunt had been. In years past, I had never even seen a buck on opening day.

Crouching beside him, I offered thanks and apology—poor compensation for what I had taken—and thought how strange this brief hunt had been. In years past, I had never even seen a buck on opening day.

The next morning, returning scraps to the forest, I paused by a pair of crisscrossed logs. The moss was festooned with clumps of fine, downy fuzz. Puzzled, I leaned over to look more closely.

Red squirrel. The ephemeral traces of another, winged, hunter’s kill.

© 2010 Tovar Cerulli

Two years ago, it was small.

Two years ago, it was small.