Too often, conversations about diet get short-circuited by the certainty and intolerance characteristic of fundamentalism.

Tag: delusions of separation

The world of hunting: Diversity in plain sight

Every once in a while, a non-hunter asks me, “What’s the hunter’s perspective on such-and-such?”

“Natural causes”: Life and death, food and fantasy

What is so compelling about the idea of life lasting until an organism gives up the ghost of its own accord?

Flesh without animals: The future of food?

What are the implications of making meat in a laboratory? What would it mean for us to take yet another step away from nature?

The good and the slobby: Hunting, logging, living

Everyone I know—hunter or non-hunter—detests slob-hunting: Animals wounded carelessly or maliciously. Bodies and body parts dumped along roadsides. Shots fired at unidentified flashes of movement. And so on. We agree that such behavior is callous and wasteful, disrespectful and dangerous.

But why should it surprise us?

Recently, while revising a chapter for my book, I found myself reflecting on a couple of points made by writer and hunter Ted Kerasote in his essay “Restoring the Older Knowledge,” which I first came across in A Hunter’s Heart.

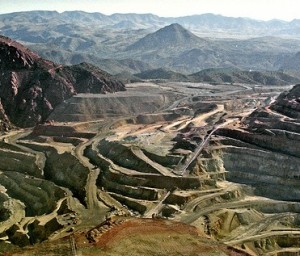

Kerasote notes that disrespect for nature and animals is not unique to thoughtless hunters. As a whole, he argues, our society operates with little regard for its impacts. From rapacious development, logging, and strip-mining to ecologically devastating agricultural practices and the application of toxic herbicides to suburban lawns, we inflict enormous damage. We do all kinds of things that are callous and wasteful, disrespectful and dangerous.

Kerasote argues, in short, that bad behavior among hunters is merely one facet of larger cultural patterns. It may be particularly visible and disturbing—for it is willful and impacts animals in an obvious, direct way—and it may therefore serve as a kind of lightning rod for disapproval, but it is not particularly unusual.

This doesn’t excuse such behavior. But it gives us a wider lens through which to see.

It helps me understand, for instance, why the question “Are you pro-hunting?” makes no sense to me.

One parallel: I have worked as a logger. If someone asks me whether I am “pro-logging,” I would say it depends. Do I approve of harvesting trees in a thoughtful, sustainable manner? Sure. Do I approve of laying waste to vast tracts of forest habitat? No.

Another parallel: I have also worked as a builder. If someone asks me whether I am “pro-construction,” I would say it depends. Do I approve of the modest timber-frame home my neighbor built for his family? Sure. Do I approve of starter castles, condominiums, and strip malls gobbling up high-quality farmland? No.

Now I hunt. Do I approve of killing a deer with as clean a shot as possible and eating the venison? Sure. Do I approve of shooting a couple hares for nothing more than amusement and leaving their bodies in the woods? Hell, no. (For lack of a wanton-waste law, I believe this remains legal in Vermont. And, yes, some people do it.)

Logging, construction, agriculture, hunting, you name it: Any activity can perpetuate the worst of who we are—humans at their greediest and most devastating. Or it can encourage the best of who we are—humans at their wisest and most respectful.

© 2011 Tovar Cerulli

Deer: Part of every stew, every salad, every stir-fry

Venison, a forester friend tells me, is the best way he knows to eat trees. He points out that whitetails do a dandy job of converting cellulose into protein.

When Cath and I sit down to a bowl of venison stew, we are eating more than potato, carrot, and deer. We are also eating maple seedlings and cedar twigs. We are eating clover from a nearby meadow and corn from the edge of a farm field. We might even be eating hosta leaves and daylily buds from our own flower gardens.

If we lived thirty miles south of here, the whitetails—and thus we—we would be eating many more acorns.

If we lived where soy crops were common, they and we would be eating many more soybeans. (Given deer’s fondness for soy, I think it’s fair to consider Illinois venison a highly metabolized form of tofu.)

In a sense, though, the flip side is also true.

In my latter days as a vegan, I was shocked to learn how many whitetails are killed by farmers. Considering that deer were being shot to bring us tofu, how vegetarian were our stir-fries? Considering that they were even being shot to bring us greens and strawberries from the organic farm just down the road, how vegetarian were any of our meals?

I was also fascinated to learn about the role that agriculture played in the politics of early deer management.

Take Vermont, for instance: In 1897, when the state legislature allowed deer hunting for the first time in three decades, the move was made largely in response to farmers’ complaints about crop losses as the nearly exterminated whitetail began to recover. Up through 1920, the regulation of deer hunting in Vermont—for both bucks and does—was largely determined by agricultural interests and was aimed at keeping deer numbers low.

By 1920, though, hunting was becoming popular. The political tide had begun to turn and the Vermont legislature established bucks-only regulations that allowed the whitetail population to grow.

As a vegan, I could have argued that hunters themselves created the present situation—in which the successful cultivation of just about every American crop depends on killing deer. I could have pointed out that deer would still be scarce today if farmers had had their way.

But what would I have been advocating for? More intensive hunting in the past, to relieve me of a moral quandary in the present?

No matter how I sliced it, deer would always accompany me at the dinner table.

Note: I got thinking about this post after reading a recent piece by Al Cambronne, wherein I learned one more thing I didn’t want to know about the U.S. beef industry. If chicken droppings don’t strike you as a taste treat, you might not want to know either.

© 2011 Tovar Cerulli

Adult-onset hunting: Know the signs

Experts have not yet determined whether Adult-Onset Hunting™ (AOH) is an epidemic. What they do know is that thousands of people are afflicted.

Experts have not yet determined whether Adult-Onset Hunting™ (AOH) is an epidemic. What they do know is that thousands of people are afflicted.

More than a year ago, it was known—and reported in a widely read New York Times article—that a growing number of U.S. citizens had the condition. According to a recent article in Toronto’s National Post, a number of Canadian citizens have contracted it as well. The geographic epicenter is unknown. Though early reports suggested that AOH is most commonly contracted in cities, recent research indicates that it is even more virulent in rural areas.

More than a year ago, it was known—and reported in a widely read New York Times article—that a growing number of U.S. citizens had the condition. According to a recent article in Toronto’s National Post, a number of Canadian citizens have contracted it as well. The geographic epicenter is unknown. Though early reports suggested that AOH is most commonly contracted in cities, recent research indicates that it is even more virulent in rural areas.

Experts suspect that AOH may have lain dormant in the American psyche for generations, feeding off 19th-century stories about Daniel Boone.

The most recent outbreak appears to be a mutation, triggered in part by widespread interest in knowing more about one’s food sources than is psychologically healthy. One pathological example often cited by both experts and adult-onset hunters is journalist Michael Pollan’s twin desires to visit cattle feedlots and to shoot a wild pig.

The most recent outbreak appears to be a mutation, triggered in part by widespread interest in knowing more about one’s food sources than is psychologically healthy. One pathological example often cited by both experts and adult-onset hunters is journalist Michael Pollan’s twin desires to visit cattle feedlots and to shoot a wild pig.

When fully developed, the primary symptoms of AOH are unmistakable: an otherwise normal, heretofore-non-hunting adult repeatedly goes to woods, fields, or marshes with a deadly implement in hand, intent on killing a wild animal.

Other potential symptoms include (1) a feeling of connection to nature, to one’s food, and to one’s hunter-gatherer ancestors, and (2) a re-calibration of one’s beliefs about hunting. Previous beliefs may suffer from atrophy, seizures, and even death, especially when an anti-hunter contracts AOH.

Knowing the early warning signs may protect you or a loved one from the worst effects. These early signs include:

- Excessive reading about the production of industrial food, especially factory meat.

- Esophageal spasms upon learning that the average pound of supermarket ground chuck contains meat from several dozen animals slaughtered in five different states.

Sudden bouts of wondering why the local food co-op—with its cooler full of local, organic, free-range meats—doesn’t sell hunting licenses.

Sudden bouts of wondering why the local food co-op—with its cooler full of local, organic, free-range meats—doesn’t sell hunting licenses.- Compulsive eating of “real food” purchased directly from farmers.

- Recurrent realizations that farmers are killing deer and woodchucks to keep organic greens on your plate.

- Impaired ability to find meaning in chicken nuggets or tofu dogs.

- Insistence on a literal reading of Woody Allen’s dictum “Nature is like an enormous restaurant.”

- An uncharacteristic compulsion to initiate dinner conversation about firearms.

- Impaired ability to see humans as separate from the rest of nature.

- Repeated contact with real, live hunters (experts suspect that AOH is highly contagious, though transmission mechanisms are not yet fully understood).

Early diagnosis is problematic, as other potential warning signs include interests in hiking, gardening, fishing, mushroom hunting, raising chickens, cooking, and eating. Even vegetarianism can be a precursor condition, particularly if your acupuncturist has recommended that you add animal protein to your diet.

Alarmingly, growing up in a non-hunting or anti-hunting family does not guarantee immunity.

Experts have begun searching for a genetic marker indicating a predisposition for AOH. Until an accurate test is available, researchers recommend following these guidelines:

- If you or someone you know exhibits 0-3 of the above signs, the risk of adult-onset hunting may be low. You are urged to watch for further symptoms.

- If 4-6 of the above signs are present, immediate action is required to prevent a full-blown case of AOH. Recommended precautions include (A) obstinate refusal to think about where one’s food comes from, especially any meat consumed, and (B) at least one-half hour per day of reading about how humans are, in fact, extraterrestrials.

- If 7-10 of the above signs are exhibited, adult-onset hunting is already entrenched. Primary symptoms will begin to appear in a matter of weeks. Sign up for a hunter education course as soon as possible and find a hunter willing to show you the ropes.

There is no known cure.

© 2011 Tovar Cerulli