Every once in a while, a non-hunter asks me, “What’s the hunter’s perspective on such-and-such?”

Tag: conservation

When tree-huggers hunt: An update on AOH

The spread of Adult-Onset Hunting (AOH) continues to worry experts.

A hunting culture in decline: Causes and consequences

We conserve and protect what we care about. If we don’t care much, where in our hearts can a serious conservation ethic possibly take root?

The ‘sport’ of hunting: Why I don’t call it that

In a world like ours, where discussions of hunting are already full of pitfalls and confusions, “sport” and “recreation” only get in the way.

Food in an ideal world

What would your ideal, sustainable world look like?

The good and the slobby: Hunting, logging, living

Everyone I know—hunter or non-hunter—detests slob-hunting: Animals wounded carelessly or maliciously. Bodies and body parts dumped along roadsides. Shots fired at unidentified flashes of movement. And so on. We agree that such behavior is callous and wasteful, disrespectful and dangerous.

But why should it surprise us?

Recently, while revising a chapter for my book, I found myself reflecting on a couple of points made by writer and hunter Ted Kerasote in his essay “Restoring the Older Knowledge,” which I first came across in A Hunter’s Heart.

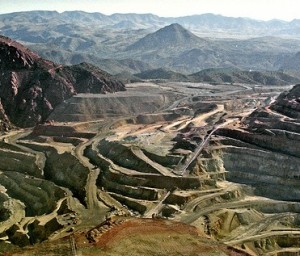

Kerasote notes that disrespect for nature and animals is not unique to thoughtless hunters. As a whole, he argues, our society operates with little regard for its impacts. From rapacious development, logging, and strip-mining to ecologically devastating agricultural practices and the application of toxic herbicides to suburban lawns, we inflict enormous damage. We do all kinds of things that are callous and wasteful, disrespectful and dangerous.

Kerasote argues, in short, that bad behavior among hunters is merely one facet of larger cultural patterns. It may be particularly visible and disturbing—for it is willful and impacts animals in an obvious, direct way—and it may therefore serve as a kind of lightning rod for disapproval, but it is not particularly unusual.

This doesn’t excuse such behavior. But it gives us a wider lens through which to see.

It helps me understand, for instance, why the question “Are you pro-hunting?” makes no sense to me.

One parallel: I have worked as a logger. If someone asks me whether I am “pro-logging,” I would say it depends. Do I approve of harvesting trees in a thoughtful, sustainable manner? Sure. Do I approve of laying waste to vast tracts of forest habitat? No.

Another parallel: I have also worked as a builder. If someone asks me whether I am “pro-construction,” I would say it depends. Do I approve of the modest timber-frame home my neighbor built for his family? Sure. Do I approve of starter castles, condominiums, and strip malls gobbling up high-quality farmland? No.

Now I hunt. Do I approve of killing a deer with as clean a shot as possible and eating the venison? Sure. Do I approve of shooting a couple hares for nothing more than amusement and leaving their bodies in the woods? Hell, no. (For lack of a wanton-waste law, I believe this remains legal in Vermont. And, yes, some people do it.)

Logging, construction, agriculture, hunting, you name it: Any activity can perpetuate the worst of who we are—humans at their greediest and most devastating. Or it can encourage the best of who we are—humans at their wisest and most respectful.

© 2011 Tovar Cerulli

Mother Nature’s Child (or Girl the Hunter)

Even before the film started, my antennae were up.

Even before the film started, my antennae were up.

Cath and I had gone to the January 25th screening of Mother Nature’s Child: Growing Outdoors in the Media Age out of general curiosity. The documentary’s message would, I expected, be much like that presented by Richard Louv’s compelling book Last Child in the Woods.

In her brief remarks before the lights went down, however, filmmaker Camilla Rockwell had piqued a more specific interest. She said that certain parts of the film were “edgy.” She would be curious to hear how people felt about them.

What would be “edgy” in a documentary about connecting kids to nature?

My gut gave one answer: hunting.

In Louv’s book, I recalled, several pages were devoted to “The Case for Fishing and Hunting.” Louv wrote that these activities “remain among the last ways that the young learn of the mystery and moral complexity of nature in a way that no videotape can convey.” As a non-hunting angler, though, his focus was on fishing. Hunting remained in the background.

In Louv’s book, I recalled, several pages were devoted to “The Case for Fishing and Hunting.” Louv wrote that these activities “remain among the last ways that the young learn of the mystery and moral complexity of nature in a way that no videotape can convey.” As a non-hunting angler, though, his focus was on fishing. Hunting remained in the background.

Settling into my seat, I enjoyed the first half of the film. It’s a well-crafted piece, blending footage of young people outdoors with excerpts from interviews with adults. We saw suburban kids running through the woods and crawling through hollow logs, their voices high with excitement. We saw urban teenagers planting gardens and learning to fly-fish. We heard from teachers, parents, and researchers.

Watching and listening, I was reminded just how crucial interaction with the natural world is for children’s physical, emotional, mental, and spiritual health. I wondered, not for the first time, who I would be today if I had not spent my boyhood summers almost entirely outdoors, wandering the woods, fishing for brook trout, catching tadpoles and bullfrogs.

And then, halfway through the film, there she was: a girl about ten years old, headed to the Vermont woods with her grandfather—in blaze orange.

Sitting there in the Montpelier’s independent theater, The Savoy, we watched the girl handling a rifle. We watched her waiting in the woods. We saw clips from interviews: Nancy Bell of The Conservation Fund talking about her respect for animals and why she hunts, Jon Young talking about how close contact with nature helps young people confront deep questions concerning life and death. Finally, we saw a still image of girl and grandfather. Beside them hung a dead deer: her first.

Fifteen years ago, I would have been horrified. Killing animals, I would have argued, has nothing to do with encouraging healthy relationships with nature, especially for kids.

Now, I see it differently. The filmmakers—both of them non-hunters—have given us a fine documentary about children’s relationships with the natural world. They have also given us a stereotype buster: women and girls hunt, and environmentalists, too! Perhaps most importantly, they have given us a great conversation starter.

The film opens a door for hunters and non-hunters to talk about hunting. Why do some of us hunt? What is it about hunting that others find revolting? Is it helpful to distinguish between stereotypes and first-hand experiences? Is it helpful for non-hunters to hear from actual hunters about how they relate to nature and animals? And, of course: What roles can or should hunting play in young people’s lives?

The film also opens a door for hunters and non-hunters to talk about our shared love of nature. It’s high time, after all, that conservationists—hunters, non-hunters, and anti-hunters—stopped lobbing political firebombs at each other.

It’s time we heeded the warning issued by Richard Nelson in his introduction to A Hunter’s Heart: “After we’ve lost a natural place, it’s gone for everyone—hikers, campers, boaters, bicyclists, animal watchers, fishers, hunters, and wildlife—a complete and absolutely democratic tragedy of emptiness.” Unless we work together, how can we insure that there will be natural places left for our children to relate to?

In the post-screening discussion, it so happens, not one person drew attention to the segment on hunting.

No, I take that back. One person did, indirectly. A man stood up to say that his young son, who appeared in the film, has now taken hunter safety and has put both squirrel and rabbit on the family dinner table. The father—a non-hunter (so far)—made it clear: connections with nature, including hunting, have done the boy nothing but good.

Notes: If you know of film festivals, schools, or outdoor education centers that might be interested in showing the film (or buying the DVD), please mention it to them. If you happen to live near any of these upcoming screenings, check it out in person:

- 3/17 – Vermont Institute of Natural Science, Quechee, VT

- 3/24 – CT Outdoor & Environ. Educ. Assn Conference, New Britain, CT

- 3/25 – Environmental Film Festival, Washington, DC

- 3/26 – Green Mountain Film Festival, Montpelier, VT

- 4/5 – Springfield Conservation Nature Center, Springfield, MO

- 5/18 – Shelburne Farms, Shelburne, VT

To learn more about Richard Louv’s work, visit the Children & Nature Network.

© 2011 Tovar Cerulli