Seeing a neighbor coming down the woods trail, I winced.

Seeing a neighbor coming down the woods trail, I winced.

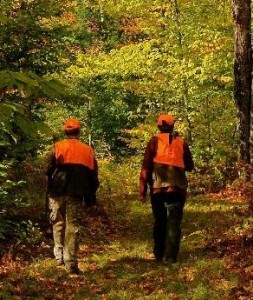

There I was, dressed in camo with a bow in hand, headed home after a morning hunt. And here he came, walking his dog.

I suspected that he, like most of my friends and acquaintances, wasn’t keen on hunting. I could hardly blame him. I had long deplored the killing of animals for food, let alone for sport.

Though I knew a respectful hunter or two, my predominant opinions had been rooted in stereotypes reinforced by personal experience: Cath’s tires slashed after we had put up a no-hunting sign, deer parts dumped alongside our road each autumn, and more.

Now, in my first autumn afield, I was still uncertain how I felt about hunting, even my own. I imagined I would have a clearer sense of it after I killed my first deer.

As my neighbor drew near, I could see surprise on his face.

“It is you,” he said. “I thought, ‘It’s some redneck out hunting and I need to watch my back.’ But no, it’s you out hunting and I need to watch my back.”

We had a polite if awkward chat. Then, only half-joking, he reminded me that he would be in the woods for a while and that his dog looked like a deer. (It would, I thought, be impossible to mistake her for anything but a young, frenetic golden retriever.) And we parted ways.

I felt that same awkwardness three years later, when my first hunting essay was published. I knew the magazine’s readership wasn’t entirely hostile to hunting. The editor sometimes wrote short pieces about his experiences in deer season. But it felt strange to publicly announce my new pursuit. Would acquaintances see the piece and be shocked? Would they give me a hard time?

I felt that same awkwardness three years later, when my first hunting essay was published. I knew the magazine’s readership wasn’t entirely hostile to hunting. The editor sometimes wrote short pieces about his experiences in deer season. But it felt strange to publicly announce my new pursuit. Would acquaintances see the piece and be shocked? Would they give me a hard time?

Thankfully, the essay sparked no negative response. What little feedback I got was positive: an enthusiastic phone message from a conservationist friend here in Vermont, an appreciative letter-to-the-editor from a hunter in upstate New York.

I breathed more easily. I would go about my business quietly now.

In the woods, I would rarely be seen.

In my writing, I would stick to other subjects. That first, brief essay had said all I wanted to say about hunting. There was no need to return to the topic, broadcasting news of my transmogrification.

I wasn’t ashamed of hunting. I didn’t need to hide it. But it wasn’t something I wanted my name to be associated with too strongly.

Heaven forbid it should get around on the internet.

© 2010 Tovar Cerulli

Two weeks ago, I got an email from

Two weeks ago, I got an email from  In the periphery of my mind, the antlers registered: maybe six points, probably a little bigger than the five-pointer I had shot some fifty yards from here, the year before.

In the periphery of my mind, the antlers registered: maybe six points, probably a little bigger than the five-pointer I had shot some fifty yards from here, the year before. Yet I did keep the skull and antlers: As things of stark beauty. As a reminder of that hunt. As a reminder of the biggest deer I ever expect—or feel any need—to kill.

Yet I did keep the skull and antlers: As things of stark beauty. As a reminder of that hunt. As a reminder of the biggest deer I ever expect—or feel any need—to kill.