Blind Men and the Elephant of Conservation:

Toward Ideological Diversity

The Aldo Leopold Foundation, 2016

As conservationists, we take it for granted that diversity is good. Biological diversity, at least.

We know that diverse, intact ecosystems are adaptable and resilient, benefiting not only us but all members of what Leopold called “the land community.” We take it on faith that all community members should be respected and that they have, as he put it, an inherent “right to continued existence.”

When I walk down to the beaver pond near home and look out at the water and surrounding land, I know that each plant, fungus, insect, amphibian, reptile, fish, bird, and mammal—even each unseen microbe in the soil—is part of that community, part of a larger, dynamic, evolving organism. As such, each deserves my respect: pine and alder, mayfly and jewelwing, salamander and turtle, minnow and trout, heron and mallard, mouse and coyote.

Concerning ideological and cultural diversity, we are ambivalent at best.

When we walk into a public meeting and look around at those who have gathered, we may not recognize each person and organization as part of the larger, dynamic, evolving endeavor called conservation. We may not feel that each deserves our respect: wildlife manager and conservation biologist, environmentalist and animal-rights advocate, state legislator and tribal chairman, rural hunter and suburban angler, black farmer and white rancher.

The idea of biodiversity, like Leopold’s related vision of a land ethic, is guided by the principle of inclusivity: by the recognition that all members of the land community belong to it and must be respected as part of it. As Leopold took pains to point out, this principle extends beyond the practical, beyond any material benefits that may accrue to us. It is rooted more deeply in a philosophical commitment to a way of belonging to the community.

What if we were to take ideological and cultural diversity just as seriously? What if, guided by the principle of inclusivity, we were to cultivate respect for diverse viewpoints as part of the conservation community? What if we were to commit to an ideological and cultural conscience parallel to an ecological conscience?

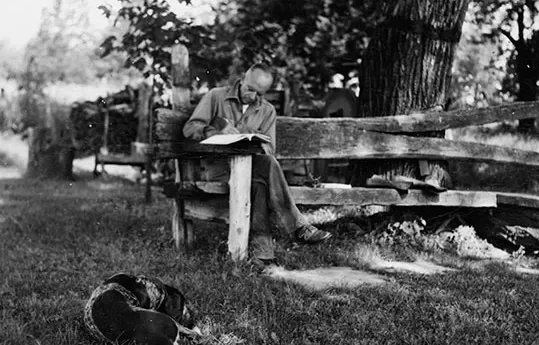

“There are two things that interest me,” Leopold once wrote, “the relation of people to each other, and the relation of people to land.”

This line is often quoted. It is not so often taken seriously. In most cases, our attention remains focused on the land half of the dictum.

Yet we remain in dire need of better relations among people. We face a perennial choice between common ground and battle ground, between the centripetal forces drawing us toward what has been called the “radical center” and the centrifugal forces threatening to tear us apart. We face a choice between focusing on what connects us and focusing on what divides us. Like ecologists studying patterns in nature, we cannot afford to be inattentive to parts of the conservation community, to ignore links among those parts, or to disrespect community members whose usefulness is not immediately apparent to us.

In ecological and biological terms, we know the shortcomings of uniformity. Monocultures lack the species diversity necessary for adaptation and resilience. Likewise, isolated populations of a given species lack the genetic diversity necessary for long-term health and survival. Uniformity, in short, leads to instability and fragility.

Though the analogy is imperfect, ideological and cultural uniformity has similar shortcomings. Human monocultures, in which diverse views are suppressed or absent, lead to certainty and narrow-mindedness. Like proverbial blind men, committed to our partial and sectarian understandings of the elephant called conservation, we lack the diversity of perspective necessary for adaptation and efficacy.

What happens when conservation groups become intolerant of ideological and cultural diversity? What happens when we develop too much faith in one way of thinking, when we get entrenched in our own cultural silos and lose touch with the rest of the world? What happens, for instance, when a hunting-conservation organization becomes so invested in particular views that it begins avoiding language that might be heard as “green” or “environmental”? What happens when an environmental organization becomes so invested in other views that it begins avoiding collaboration with hunters or ranchers?

Conservation becomes fragmented and destabilized. Each sub-community’s aims become narrower in scope, more self-serving, more ephemeral. Competition with other sub-communities becomes a central focus. Our attention and energy get distracted by infighting. One group’s triumph becomes another group’s defeat, or—more likely—its next lawsuit.

We slip into polarized habits of mind. We begin to think in simple binaries: blue versus red, urban versus rural. We accuse each other of ignorance. We lose interest in, and even the capacity to perceive, common ground. The integral wholeness of conservation, even the possibility of such wholeness, is largely forgotten.

We tell stories about our differences. Hunter conservationists, the story goes, care about animals only as populations. Animal welfarists, the story goes, care about animals only as individuals. Ranchers and loggers, the story goes, care about land only as a source of profit. Wilderness proponents and endangered species advocates, the story goes, care nothing for the people who work the land.

Most of a century ago, writing of hunter and non-hunter conservationists, Leopold emphasized the need to question our insular thinking: “With both sides in doubt as to the infallibility of their own past dogmas, we might actually hang together long enough to save some wild life. At present, we are getting good and ready to hang separately.”

The relation of people to each other. The relation of people to land.

What if conservationists devoted equal attention to both? What if we devoted as much attention to cultural edges and changes as to ecological edges and changes? What if we devoted as much attention to geographies and histories of meaning as to geographies and histories of land?

What if we began listening? Not listening strategically, so we can refute what we hear. Not listening superficially, so we can pigeonhole the speaker. But listening carefully and deeply, with the respectful intention of understanding others’ perspectives: their experiences and perceptions, values and hopes, needs and fears, the meanings that underpin what they say.

What if we began listening with courage, willing to hear and understand beyond the confines of the familiar? What if we began listening with imagination, assuming that others’ voices, views, and stories are coherent, doing our best to step into their worlds?

Listening in these ways, we risk losing our bearings. What, after all, would happen if I understood those people, so very different from me? Who would I be? What would I do? What would the rest of my group think of me? And what, heaven forbid, if those very different people’s perceptions, values, and experiences turn out to be valid in some way? What if my own views are revealed as fallible and incomplete?

It is precisely in risking the loss of those familiar bearings that we can find new clarity and direction. Listening with courage, we can begin to recognize one another as fellow members of a dynamic, evolving community. Looking around those meeting rooms, both literal and figurative, we can begin to recognize that each of us is at least partially blind. We can begin to understand that we need each other to see a larger picture.

© 2016 Tovar Cerulli